|

Rational Sines of Rational Multiples of π |

|

|

|

For which rational multiples of π is the sine rational? We have the three trivial cases |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and we wish to show that these are essentially the only distinct rational sines of rational multiples of π. One often sees very succinct “proofs” of this assertion, but they rely on propositions concerning Gaussian integers that are actually generalizations of the very assertion we wish to prove. Without providing proofs of those supporting propositions, these “proofs” are not very illuminating. Below we give a genuine proof, from scratch, and also use this opportunity to describe some useful facts about an important class of algebraic numbers and linear fractional transformations. |

|

|

|

The assertion about rational sines of rational multiples of π follows from two fundamental lemmas. The first is |

|

|

|

Lemma 1: For any rational number q the value of sin(qπ) is a root of a monic polynomial with integer coefficients. |

|

|

|

Proof: For any given linear fractional transformation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

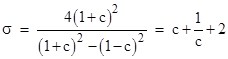

where a,b,c,d are complex constants, we define the similarity parameter |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The iterates in the complex plane of two linear fractional transformations are geometrically similar if and only if those two transformations have the same similarity parameter. (See the article on Linear Fractional Transformations for a derivation.) Now we consider the function |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

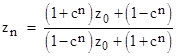

where c is a constant. For any arbitrary initial value z0 let zn denote the nth iterate of f(z). It’s easy to show by induction that |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In order for this sequence of iterates to be cyclical with period m we must have cm = 1 for some integer m, so the constant c must have unit magnitude and its phase angle must be a rational multiple of 2π. Specifically, c must be of the form |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

for n = 1, 2, …, or m–1. The similarity parameter of this transformation is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus the similarity parameter for transformations that are cyclic with period m must be equal to one of the values |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

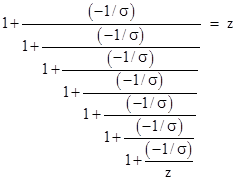

with n = 1, 2, …, or m-1. The same periodicity applies to any linear fractional transformation with one of these values of the similarity parameter, and in particular, it applies to the transformation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

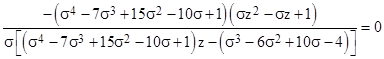

From this we can infer the polynomial whose roots are the values of σm. For example, iterating this function m=7 times beginning with the value z, and setting the result to the same value of z, we get (omitting the subscript 7 on σ for convenience) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

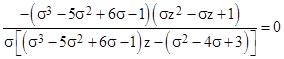

Expanding and simplifying this, we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus the transformation is cyclical with period 7 (for arbitrary arguments z) if and only if the similarity parameter σ is a root of the monic polynomial with integer coefficients |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We’ve already seen that these values are 4cos(πn/7)2 for n = 1, 2, and 3, so this shows that these values are the roots of the above polynomial. If we perform the same calculation for m = 8 we get the condition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and for m = 9 we get the condition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

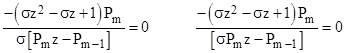

and so on. Letting Pm denote the polynomial in σ in the numerator, these expressions for odd and even m are respectively of the form |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

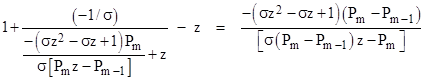

To prove that this is true for all m, and that the polynomials are all monic with integer coefficients, note that we can derive any of the conditions by simply adding z to the previous condition, applying one more iteration of the function g, and then subtracting z. Thus if m is odd the condition for σm+1 is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and if m is even the condition for σm+1 is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

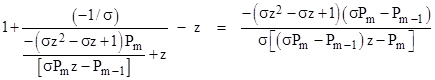

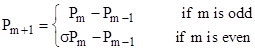

Therefore the polynomials Pj satisfy the recurrence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

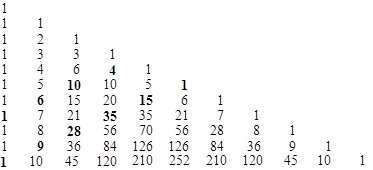

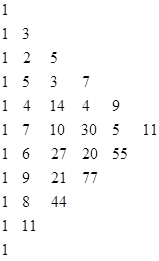

We see that each polynomial is monic with integers coefficients, so this completes the proof of Lemma 1. Incidentally, from the above recurrence it follows that the coefficients of these polynomials are diagonal elements (with alternating signs) of Pascal's triangle as shown below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For example, the five roots of the quintic x5 – 9x4 + 28x3 – 35x2 + 15x – 1 are given by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and the three roots of the cubic x3 – 6x2 + 10 – 4 are given by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Our second lemma is commonly known as “Gauss’ Lemma”, and is fundamental in the study of algebraic properties of the roots of polynomials. |

|

|

|

Lemma 2: Any root of a monic polynomial f(x) with integer coefficients must either be an integer or irrational. |

|

|

|

Proof: The proposition is trivially true for polynomials of degree 1. We will show that if the proposition is true for all polynomials of degree less than k, then it is true for polynomials of degree k, and hence by induction for all k. First, we define the degree of any real number x as the degree of the minimal monic polynomial with integer coefficients having the root x. For example, the degree of 5 is 1, whereas the degree of the square root of 5 is 2. |

|

|

|

Letting C denote the constant coefficient of f(x), we have the polynomial |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

of degree k–1, and g(x) is monic with integer coefficients. Now we posit the existence of a rational non-integer root r of the original polynomial f(x). Since r is not an integer, it must be of degree k, because it cannot be a root of any polynomial (monic with integer coefficients) of degree less than k. Now, we have f(r) = 0 and so g(r) = –C/r, from which it follows that –C/r is not an integer, because if it was, then r would be a root of the polynomial g(x)+C/r of degree k–1. Therefore we can choose an integer M such that |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Let N denote the smallest integer P such that Pg(r) is an integer. (This N exists because g(r) is rational.) It follows that N times any polynomial in r of degree k-1 is an integer, because if an integer N can clear the fractions of the monic polynomial g(r) it can also clear the fractions of any other polynomial in r (with integer coefficients) of the same degree. |

|

|

|

From the preceding it follows that N' = N [g(r) – M] is an integer, and it is smaller than N because the factor is square brackets is between 0 and 1. Furthermore, we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This too is an integer because we can express g(r)2 as a polynomial of degree k-1 simply by reducing every higher power of r by substituting from the expression for rk given by f(r) = 0. But this contradicts the fact that N is the smallest integer P such that Pg(r) is an integer. Therefore, f(x) cannot have a rational non-integer root, so the proof of Lemma 2 is complete. |

|

|

|

We can now easily prove our original proposition, which asserts that the only rational sines of rational multiples of π are the three cases sin(0) = 0, sin(π/6) = 1/2, and sin(π/2) = 1. |

|

|

|

Proof: In general if sin(x) is rational then so is sin(x)2 and hence so is cos(x)2 = 1 – sin(x)2. Therefore, if sin(πn/d) is rational, so is 4cos(πn/d)2, so it is sufficient to determine the values of n/d such that 4cos(πn/d)2 is rational. By Lemma 1, the latter values are all roots of monic polynomials with integer coefficients, and by Lemma 2 the only rational roots of such polynomials are integers. But the absolute value of 4cos(πn/d)2 cannot exceed 4, so the only possible rational values it can have are N = 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4. Also, since sin(x) equals the square root of 1–cos(x)2, the former can be rational only if 4-N is a square integer, which implies (since the square roots of 2 and 3 are not rational) that the only suitable values of N are 0, 3, and 4, which correspond to the arguments (up to sign) π/2, π/6, and 0 respectively. The sines of each of these values are indeed rational, and this completes the proof that these are the only rational multiples of π with rational sines. |

|

|

|

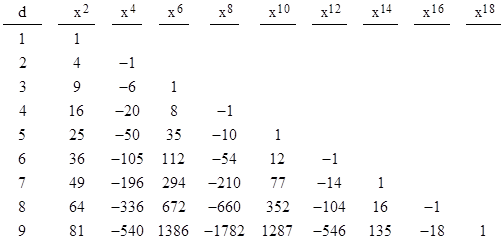

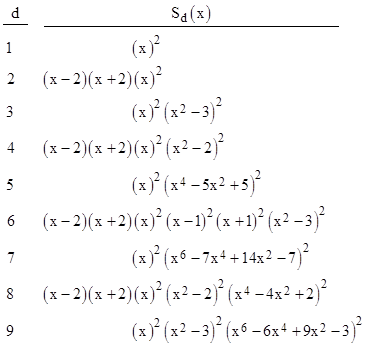

Incidentally, another approach to this proof would be to consider, for any given integer d, the polynomial whose roots are the 2d values 2sin(πn/d) with n = 0, 1, 2,.., 2d–1. Just as in the case of the quantities 4cos(πn/d)2, we find that these quantities are the roots of monic polynomials with integer coefficients. The coefficients of the first several of these polynomials are shown below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

These polynomials are closely related to the Chebyshev polynomials. We will let Sd(x) denote the dth polynomial in this table. (Of course, two of the roots of each of these equations, those corresponding to n=0 and n=d, are zero, so we could factor x2 out of each polynomial. However, we prefer to retain all the roots, for compatibility with the cosine polynomials discussed below.) The absolute values of the coefficients in this table satisfy the recurrence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For example, in the 9th row the value of 1287 is equal to (660) + 2(352) – (77). The recurrence applies to the first column as well, provided we assume a prior column filled with 2s. Since Ad,k represents the sum of all products of k double-sines from the set of values 2sin(πn/d) with n = 0 to 2d-1, excluding n=0 and n=1, the recurrence formula represents an infinite family of trigonometric identities. |

|

|

|

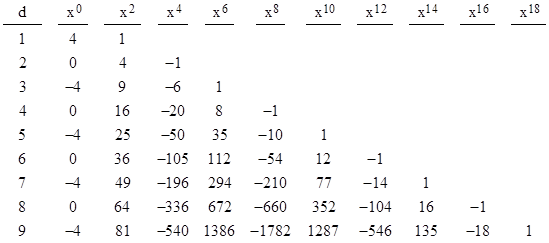

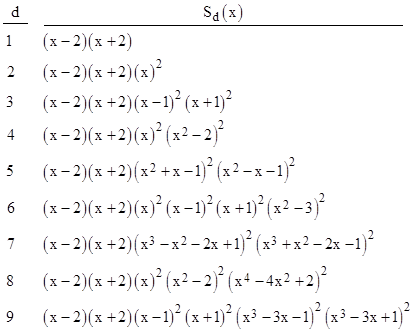

Naturally if d divides m then Sd(x) divides Sm(x). Also, for even integers d the set of values 2sin(πn/d) for n = 0, 1,.., 2d–1 is precisely the same set of values of 2cos(πn/d) for n = 0, 1, .., 2d–1, although in a different order. Therefore, if we let Cd(x) denote the polynomial whose roots are 2cos(πn/d) for n = 0, 1,.., 2d–1 we have C2j(x) = S2j(x) for all positive integers j. On the other hand, if d is odd, the values of sin(πn/d) and cos(πn/d) are shifted "half a step" from each other, so the sine and cosine polynomials are not the same. Of course, it's clear that Cd(x) must always divide S2d(x), and likewise Sd(x) must divide C2d(x). The actual coefficients for the polynomials Cd(x) are listed below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When evaluating either sin(πn/d) or cos(πn/d) over an entire cycle from n = 0 to 2d–1, every value occurs precisely twice (because, for example, sin(30) = sin(150)), except for the peak values, which occur in sin(πn/d) when n is even, and in cos(πn/d) for all n. Consequently, we know Sd(x) must be of the form (x–2)(x+2)p(x)2 when d is even, and of the form p(x)2 when d is odd, where p(x) is monic with integer coefficients. On the other hand, Cd(x) must always be of the form (x–2)(x+2)p(x)2. To confirm this, here are the factorizations for the first few polynomials Sd(x): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and here are the factorizations of the first few polynomials Cd(x): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

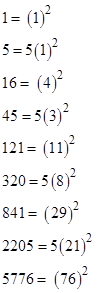

The number of "new" roots of each successive polynomial Sd(x) and Cd(x) is just the totient function f(n), i.e., the number of positive integers less than and coprime to n. As an aside, the sums of the coefficients of Sd(x) have the values |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

which are given by 2[1–cos(πk/3)]. On the other hand, the sums of the absolute values of the coefficients are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

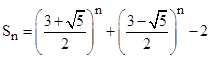

and so on. If we increase each of these values by 2 we get the sequence 3, 7, 18, 47, etc., which satisfies the homogeneous recurrence sn = 3sn–1 – sn–2, and from this we see that the above values can be expressed in closed form as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It’s also interesting to note that if we add 4 to each of the alternate terms 5, 45, 320, 2205, etc., we get the squares of 3, 7, 18, 47, etc., which exceed by 2 the original values. |

|

|

|

Had we chosen to work with polynomials whose roots are just the sines (rather than twice the sines), we would have gotten polynomials whose coefficients sum alternately to 0 and -1, and whose absolute coefficients sum to the values |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and so on. These numbers satisfy the recurrence sn = 6sn–1 – sn–2 + 2, corresponding to the Pell equation x2 – 8y2 = 1. Hence the values of sn(sn + 1)/2 are all the square triangular numbers. Also, note that adding 1 to 8 or to 9800 gives a square, and adding 1 to 244 gives 5 times a square. |

|

|

|

It’s easy to see how the polynomials Sd(x) and Cd(x) are related to the polynomials whose roots are 4cos(x)2 that we discussed previously. Recall that the coefficients of the latter polynomials were diagonals of Pascal’s triangle. Using the relations sin(x)2 = 1 – cos(x)2 we can immediately determine the coefficients of the polynomials whose roots are 4sin(x)2 by simply substituting 4–x in place of x in the polynomials whose roots are 4cos(x)2. This gives the following array, analogous to Pascal’s triangle. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For example, the five roots of the quintic x5 – 11x4 + 44x3 – 77x2 + 75x – 71 are given by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It’s interesting that the coefficients in the pth diagonal (after the first) where p is a prime are all divisible by p. |

|

|

|

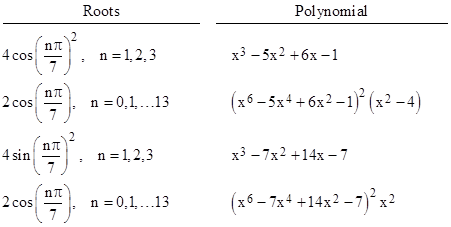

Now, the relationships between the various polynomials described above are depicted by means of examples in the table the following table. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The polynomials in just the doubled sines and cosines occur with both signs, so the paired factors combine to give four times the squared sines and cosines, which is why the sets of polynomials share the common factors (after replacing x with x2). Also, since we’ve taken all roots of the doubled sine and cosine functions for n from 0 to 2d–1, all the squared roots are duplicated, accounting for the squaring of the common factors. Of course, the extraneous factors x2 – 4 and x2 are due our inclusion of the trivial roots with n = 0 and n = d. Thus after rigorously deriving the polynomials for the quantities 4cos(πn/d)2, all the other sets of polynomials can be rigorously deduced by simple substitutions. |

|

|