|

4.5 Conventional Wisdom |

|

|

|

This, however, is thought to be a mere strain upon the text, for the words are these: ‘That all true believers break their eggs at the convenient end’, and which end is the convenient end, seems, in my humble opinion, to be left to every man’s conscience… |

|

Jonathan Swift, 1726 |

|

|

|

It is a matter of empirical fact that the speed of light is invariant in terms of inertial coordinates (as defined in Section 1.3), and yet the invariance of the speed of light is often said to be a matter of convention − as indeed it is. The empirical fact refers to the speed of light in terms of inertial coordinates, but the decision to define speeds in terms of inertial coordinates is conventional. It’s trivial to define systems of space and time coordinates in terms of which the speed of light is not invariant, but we ordinarily choose to describe events in terms of inertial coordinates, partly because of the invariance of light speed in those coordinates. This invariance would be tautological (given source independence) if inertial coordinate systems were simply defined as the systems in terms of which the speed of light is invariant. However, as discussed in Section 1.3, the class of inertial coordinate systems, including the time coordinate, is actually defined in purely mechanical terms, without reference to the propagation of light. They are the coordinate systems in terms of which mechanical inertia is homogeneous and isotropic, which are the necessary and sufficient conditions for Newton’s three laws of motion to be valid, at least quasi-statically. The empirical invariance of light speed with respect to this class of coordinate systems is a non-trivial empirical fact, but nothing requires us to define “velocity” in terms of inertial coordinate systems. Such systems cannot claim to have any a priori status as the “true” class of coordinates. Despite the undeniable success of the principle of inertia as a basis for organizing our understanding of the processes of nature, it is nevertheless a convention. |

|

|

|

The conventionalist view can be traced back to Poincare, who wrote in "The Measure of Time" in 1898 |

|

|

|

... we have no direct intuition of simultaneity, nor of the equality of two durations. The simultaneity of two events or the order of their succession, as well as the equality of two time intervals, are to be defined in such a way that the statements of the natural laws are as simple as possible. |

|

|

|

In the same paper, Poincare described the use of light rays, together with the convention that the speed of light is invariant and the same in all directions, as one way of giving an operational meaning to the concept of simultaneity. In his book "Science and Hypothesis" (1902) he summarized his view of time by saying “there is no absolute time”, and that statements about relative sizes of different time intervals and about the simultaneity of two events occurring in two different places can only acquire meaning by a convention. Poincare's views had a strong influence on the young Einstein, who avidly read "Science and Hypothesis" with his friends in the self-styled "Olympia Academy". Solovine remembered that this book "profoundly impressed us, and left us breathless for weeks on end". Indeed we find in Einstein's 1905 paper on special relativity the statement |

|

|

|

A time common to A and B can now be determined by establishing by definition that the time needed for the light to travel from A to B is equal to the time it needs to travel from B to A. |

|

|

|

He later wrote that this is “neither a supposition nor a hypothesis about the physical nature of light, but a stipulation which I can make of my own freewill in order to arrive at a definition of simultaneity”. Strictly speaking, an operational definition of simultaneity, based on mechanical inertia, was already implicit in Einstein’s prior stipulation of “coordinates in which the equations of Newtonian mechanics hold good” (to the first approximation), but he chose to emphasize the isotropy of light. |

|

|

|

This concept of simultaneity is also embodied in Einstein's second "principle", which asserts the invariance of light speed. Throughout the writings of Poincare, Einstein, and others, we see the invariance of the speed of light referred to as a convention, a definition, a stipulation, a free choice, an assumption, a postulate, and a principle... as well as an empirical fact. There is no conflict between these characterizations, because the convention (definition, stipulation, free choice, principle) that Poincare and Einstein were referring to is nothing other than the decision to use inertial coordinate systems, and once this decision has been made, the invariance of light speed is an empirical fact. As Poincare said, we naturally choose our coordinate systems "in such a way that the statements of the natural laws are as simple as possible", and this almost invariably means inertial coordinates. It was the great achievement of Galileo, Descartes, Huygens, and Newton to identify the principle of inertia as the basis for resolving and coordinating physical phenomena. Unfortunately this insight is often disguised by the manner in which it is traditionally presented. The beginning physics student is typically expected to accept uncritically an intuitive notion of "uniformly moving" time and space coordinate systems, and is then told that Newton's laws of motion happen to be true with respect to those "inertial" systems. It is more meaningful to say that we define inertial coordinate systems as those systems in terms of which Newton's laws of motion are valid. We naturally coordinatize events and organize our perceptions in such a way as to maximize symmetry, and for the motion of material objects the most important symmetries are the isotropy of inertia, the conservation of momentum, the law of equal action and re-action, and so on. Newtonian physics is organized entirely upon the principle of inertia, and the basic underlying hypothesis is that for any object in any state of motion there exists a system of coordinates in terms of which the object is instantaneously at rest and inertia is homogeneous and isotropic (implying that Newton's laws of motion are at least quasi-statically valid). |

|

|

|

The empirical validity of this remarkable hypothesis accounts for all the tremendous success of Newtonian physics. As discussed in Section 1.3, the specification of a particular state of motion, combined with the requirement for inertia to be homogeneous and isotropic, completely determines a system of coordinates (up to insignificant scale factors, re-orientations, etc.), and such a system is called an inertial system of coordinates. Such coordinate systems can be established unambiguously by purely mechanical means (neglecting the equivalence principle and associated complications in the presence of gravity). The assumption of inertial isotropy with respect to a given state of motion suffices to establishes the loci of inertial simultaneity for that state of motion. Poincare and Einstein rightly noted the conventionality of this simultaneity definition because they were not pre-supposing the choice of inertial simultaneity. In other words, we are not required to use inertial coordinates. We simply choose, of our own free will, to use inertial coordinates − with the corresponding inertial definition of simultaneity − because this renders the statement of physical laws and the descriptions of physical phenomena as simple and perspicuous as possible, by taking advantage of the maximum possible symmetry. |

|

|

|

It should be emphasized that inertial coordinates are not entirely characterized by the quality of being unaccelerated, i.e., by the requirement that isolated objects move uniformly in a straight line. It's also necessary to require the unique simultaneity convention that renders mechanical inertia isotropic (the same in all spatial directions), which amounts to the stipulation of equal one-way speeds for the propagation of physically identical actions. These comments are fully applicable to the Newtonian concept of space, time, and inertial reference frames. Given two objects in relative motion we can define two systems of inertial coordinates in which the respective objects are at rest, and we can orient these coordinates so the relative motion is purely in the x direction. Let t,x and tʹ,xʹ denote these two systems of inertial coordinates. That such coordinates exist is the main physical hypothesis underlying Galilean physics. An auxiliary hypothesis – one that was not always clearly recognized – concerns the relationship between two such systems of inertial coordinates, given that they exist. Galileo assumed that if the coordinates x,t of an event are known, and if the two inertial coordinate systems are the rest frames of objects moving with a relative speed of v, then the coordinates of that event in terms of the other system (with suitable choice of origins) are tʹ = t, xʹ = x − vt. Viewed in the abstract, this is a rather peculiar and asymmetrical assumption, although it is admittedly borne out by experience − at least to the precision of measurement available to Galileo. However, we now know, empirically, that the relation between relatively moving systems of inertial coordinates has the symmetrical form tʹ = (t − vx)γ and xʹ = (x − vt)γ where γ = (1−v2)−1/2 when the time and space variables are expressed in the same units such that the constant (3)108 meters/second equals unity. It follows that the one-way (not just the two-way) speed of light is invariant and isotropic with respect to any and every system of inertial coordinates. |

|

|

|

The empirical content of this statement is simply that the propagation of light is isotropic with respect to the same class of coordinate systems in terms of which mechanical inertia is isotropic. This is consistent with the fact that light itself is an inertial phenomenon, e.g., it conveys momentum. In fact, the inertia of light can be seen as a common thread running through three of the famous papers published by Einstein in 1905. In the paper entitled "On a Heuristic Point of View Concerning the Production and Transformation of Light" Einstein advocated a conception of light as tiny quanta of energy and momentum, somewhat reminiscent of Newton's inertial corpuscles of light. It's clear that Einstein already understood that the conception of light as a classical wave is incomplete. In the paper entitled "Does the Inertia of a Body Depend on its Energy Content?" he explicitly advanced the idea of light as an inertial phenomenon, and of course this was suggested by the fundamental ideas of the special theory of relativity presented in the paper "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies". |

|

|

|

The Galilean conception of inertial frames assumed that all such frames share a unique foliation of spacetime into "instants". Thus the relation "in the present of" constituted an equivalence relation across all frames of reference. If A is in the present of B, and B is in the present of C, then A is in the present of C. However, special relativity makes it clear that there are infinitely many distinct loci of inertial simultaneity through any given event, because inertial simultaneity depends on the velocity of the worldline through the event. The inertial coordinate systems do induce a temporal ordering on events, but only a partial one. (See the discussion of total and partial orderings in Section 1.2.) With respect to any given event we can still partition all the other events of spacetime into distinct causal regions, including "past", "present" and "future", but in addition we have the categories "future null" and "past null", and none of these constitute equivalence classes. For example, it is possible for A to be in the present of B, and B to be in the present of C, and yet A is not in the present of C. Being "in the present of" is not a transitive relation. |

|

|

|

It could be argued that a total unique temporal ordering of events is a more useful organizing principle than the isotropy of inertia, and so we should adopt a class of coordinate systems that provides a total ordering. Consider, for example, a system of time coordinates such as the one described at the beginning of Einstein’s 1905 paper (as discussed in Section 1.6): |

|

|

|

We could content ourselves with evaluating the time of events by stationing an observer with a clock at the origin of the coordinates who assigns to an event to be evaluated the corresponding position of the hands of the clock when a light signal from that event reaches him through empty space. |

|

|

|

In other words, every event on the past light cone of the clock (resting at the spatial origin) at a given instant is assigned the same time coordinate. For any given position and state of motion of the coordinate origin this gives a unique temporal ordering of events, but other positions and states of motion give other orderings. In fact, we can assign the same time coordinate to any two space-like separated events merely by placing the origin in the intersection of the future null cones of those two events. Thus we have the same partial ordering of events as does the set of inertial coordinates, and this applies to any other posited “true” temporal foliation. Nevertheless, people who regard the total temporal ordering of events as a priority for intelligibility are free to adopt such a foliation (at least in principle). This seems to have been the view of Lorentz, who wrote in 1913 about the comparative merits of the traditional Galilean and the new Einsteinian conceptions of time |

|

|

|

It depends to a large extent on the way one is accustomed to think whether one is attracted to one or another interpretation. As far as this lecturer is concerned, he finds a certain satisfaction in the older interpretations, according to which... space and time can be sharply separated, and simultaneity without further specification can be spoken of... one may perhaps appeal to our ability of imagining arbitrarily large velocities. In that way one comes very close to the concept of absolute simultaneity. |

|

|

|

Of course, the idea of "arbitrarily large velocities" already pre-supposes a concept of absolute simultaneity, so Lorentz's rationale is not especially persuasive, but it expresses the point of view of someone who places great importance on a total temporal ordering, even at the expense of inertial isotropy. Indeed one of Poincare's criticisms of Lorentz's early theory was that it sacrificed Newton's third law of equal action and re-action. Lorentz replied “But must we, in truth, worry ourselves about it?” (The law can be formally salvaged by assigning the unbalanced momentum to an undetectable ether, but then it is no longer a meaningful conservation law.) Even Poincare sometimes expressed the opinion that a total temporal ordering would always be useful enough to out-weigh other considerations, and that it would always remain a safe convention. The approach taken by Lorentz and most others may be summarized by saying that they sacrificed the physical principles of inertial relativity, isotropy, and homogeneity in order to maintain the assumed Galilean composition law. This approach, although technically serviceable, suffers from a certain inherent lack of conviction, because while asserting the ontological reality of anisotropy in all but one (unknown) frame of reference, it unavoidably requires us to disregard that assertion and arbitrarily assume one particular frame as being "the" rest frame to perform any actual calculations. |

|

|

|

Poincare and Einstein recognized that, in our descriptions of events in terms of separate space and time coordinates, we're free to select our "basis" of decomposition. This is precisely what one does when converting the description of events from one frame to another using Galilean relativity, but, as noted above, the Galilean transformation law yields coordinates in terms of which inertia is not isotropic. Hence it appeared that we could no longer maintain isotropy and homogeneity in all inertial frames together with the ability to transform descriptions from one frame to another by simply applying the appropriate basis transformation. But Einstein showed that the new observations were fully consistent with both isotropy in all inertial frames and with simple basis transformations between frames, provided we adjust our assumption about the effective metrical structure of spacetime. In effect, he showed that inertial coordinate systems are related by Lorentz transformations, which then led to a reformulation of physics in terms of the (pseudo-)metrical structure of Minkowski spacetime. |

|

|

|

Even a metrical structure is conventional in a sense, because it relies on our ontological premises. For example, the magnitude of the interval between two events may seem to be one thing but actually be another, due (perhaps) to variations in our means of observation and measurement. However, once we have agreed on the physical significance of inertial coordinate systems, the invariance of the quantity (dt)2 − (dx)2 − (dy)2 − (dz)2 also becomes physically significant. This shows the crucial importance of the very first sentence in Section 1 of Einstein's 1905 paper: |

|

|

|

Let us take a system of co-ordinates in which the equations of Newtonian mechanics hold good. |

|

|

|

Suitably qualified (as noted in Section 1.3), this immediately establishes not only the convention of simultaneity, but also the means of operationally establishing it, and its physical significance. Any observer in any state of inertial motion can throw two identical particles in opposite directions with equal force (i.e., so there is no net disturbance of the observer's state of motion), and the convention that those two particles have the same speed suffices to fully specify an entire system of space and time coordinates, which we call inertial coordinates. It is then an empirical fact − not a definition, convention, assumption, stipulation, or postulate − that the speed of light is isotropic in terms of inertial coordinates. This obviously doesn't imply that inertial coordinates are "true" in any absolute sense, but the use of inertial coordinates has proven to be immensely powerful for organizing our knowledge of physical events, and for discerning and expressing the apparent chains of causation. |

|

|

|

If a flash of light emanates from the geometrical midpoint between two spatially separate particles at rest in an inertial frame, the arrival times of the light wave at those two particles are simultaneous in terms of that rest frame’s inertial coordinates. Furthermore, we find empirically that all other physical processes are isotropic with respect to those inertial coordinates, e.g., if a sound wave emanates from the midpoint of a uniform steel beam at rest in an inertial frame, the sound reaches the two ends simultaneously in accord with this definition. If we adopt any other convention we introduce anisotropies in our descriptions of physical processes, such as sound in a uniform stationary steel beam propagating more rapidly in one direction than in the other. The isotropy of physical phenomena − including the propagation of light − is strictly a convention, but it was not introduced by special relativity, it is one of the fundamental principles which we use to organize our knowledge, and it leads us to choose inertial coordinates for the description of events. On the other hand, the isotropy of multiple distinct physical phenomena in terms of inertial coordinates is not purely conventional, because those coordinates can be defined in terms of just one of those phenomena. The value of this definition is due to the fact that a wide variety of phenomena are (empirically) isotropic with respect to the same class of coordinate systems. |

|

|

|

It could be argued that all these phenomena are, in some sense, “the same”. For example, the energy conveyed by electromagnetic waves has momentum, so it is an inertial phenomenon, and therefore it is not surprising that the propagation of such energy is isotropic in terms of inertial coordinates. From this point of view, the value of the definition of inertial coordinates is that it reveals the underlying unity of superficially dis-similar phenomena, e.g., the inertia of energy. This illustrates that our conventions and definitions are not empty, because they represent ways of organizing our knowledge to most clearly reflect the unity and symmetries of the phenomena. We could, if we wish, organize our knowledge based on the assumption of a total temporal ordering of events, but then it would be necessary to introduce a whole array of anisotropic "corrections" to the descriptions of physical phenomena. |

|

|

|

As we’ve seen, the principle of relativity constrains, but does not uniquely determine, the form of the mapping from one system of inertial coordinates to another. To fix the observable elements of a spacetime theory with respect to every standard system of inertial coordinates we require one further fact, such as the invariance of the one-way speed of light (in terms of such coordinates), the inertia of energy, or even the inversion symmetry discussed in Section 1.8. Regarding the speed of light, one might wonder if a weaker fact, invariance of the round-trip speed of light, would suffice. Consider an experiment of the type conducted by Michelson and Morley in their efforts to detect a directional variation in the speed of light, due to the motion of the Earth through the aether, in which light was presumed to have a characteristic speed. They compared the elapsed times, at the point of origin, for beams of light to complete round trips to mirrors and back in perpendicular directions. One might think it would be just as easy to measure the one-way speed of light in various directions by simply comparing the time of transmission of a pulse of light from one location to the time of reception at another location, but of course this would require us to have clocks synchronized at spatially separate locations, whereas it is precisely this synchronization that is at issue. Different synchronizations of separate clocks will result in different values for speeds. This ambiguity is avoided to some extent if we content ourselves with a comparison of round-trip speeds. (The definition of spatial distances still relies, to second order, on the choice of simultaneity, but this is typically finessed by the un-critical use of co-moving standard measuring rods). |

|

|

|

It might seem that Roemer's method of estimating the speed of light from the variations in the period between eclipses of Jupiter's moons (see Section 3.3) constituted a one-way measurement. Similarly people sometimes imagine that the one-way speed of light could be discerned by (for example) observing, from the center of a circle, pulses of light emitted uniformly by a light source moving at constant speed around the perimeter of the circle. Such methods are indeed capable of detecting certain kinds of anisotropy, but they cannot detect the anisotropy entailed by Lorentz’s ether theory, nor any of the other theories that are observationally indistinguishable from Lorentz’s theory (which itself is indistinguishable from special relativity). In any theory of this class, there is an ambiguity in the definition of a “circle” in motion, because circles contract to ellipses in the direction of motion. Likewise there is ambiguity in the definition of “uniformly-timed” pulses from a light source moving around the perimeter of a moving circle (ellipse). The combined effect of length contraction and time dilation in a Lorentzian theory is to render the anisotropies unobservable. |

|

|

|

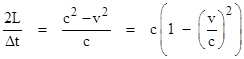

These empirically indistinguishable “theories” are in fact all the same theory, expressed in terms of different coordinate systems. Even if we agree to use coordinates in terms of which the two-way speed of light is invariant, there remains an ambiguity in the one-way speed of light, because over any closed loop the net change in each and every direction is zero. Hence we are free to use coordinate systems in terms of which the one-way speed of light is non-isotropic. Admittedly the equations expressing the laws of physics will take on a somewhat convoluted appearance when expressed in terms of these (non-isotropic) coordinates, and will contain unobservable parameters and “fictitious” forces, but such coordinates are nevertheless empirically viable. To illustrate, consider a measurement of the round-trip speed of light, assuming light travels at a constant speed c relative to some absolute medium with respect to which our laboratory is moving with a speed v. Under these assumptions, we might expect a pulse of light to travel with a speed c+v (relative to the lab) in one direction, and c−v in the opposite direction. So, if we send a beam of light over a distance L (measured by rods at rest in the lab) out to a mirror in the "c+v" direction, and it bounces back over the same distance in the "c−v" direction, the total elapsed time to complete the round trip of length 2L is |

|

|

|

|

|

Therefore, the average round-trip speed relative to the laboratory would be |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On this basis we might have expected the round-trip speed of light (in terms of local inertial coordinates) to vary with the speed of the laboratory, albeit only to the second order in v/c. The ability to detect such small effects was first achieved in the late 19th century with the development of precision interferometry. Despite the evident motion of the Earth in its orbit around the Sun, it was found that (in terms of our co-moving inertial coordinates) the quantity 2L/Δt for a pulse of light is always equal to c, even to the second order. This is the empirical basis for asserting that, in terms of our chosen systems of coordinates, the round-trip speed of light is independent of our state of (inertial) motion. However, as Einstein pointed out, this does not fully determine our choice of coordinate systems. Some further stipulation is required. According to special relativity, the coordinate systems that we normally use, in terms of which the equations of Newtonian mechanics hold good (to the first approximation), are identical to the coordinate systems in terms of which the one-way speed of light has the invariant value c. The one-way speed invariance doesn't follow from the invariance of the two-way speed of light, but it is an empirical proposition that can be proved or disproved by experiment. We simply establish a system of inertial coordinates – which entails the simultaneity relations necessary for Newton’s third law to hold good, and then measure the one-way speed of light in terms of those coordinates. But the decision to describe phenomena in terms of this special class of coordinate systems (i.e., coordinates in terms of which inertia is homogeneous and isotropic) is a free choice. The speed of light (or of anything else), both one-way and two-way, necessarily depends on our choice of coordinate systems, and is an empirical concept only given such a choice. |

|

|

|

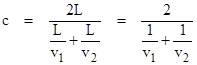

To illustrate the ambiguity, notice that we can ensure the invariance of the two-way speed of light (along a given axis) while maintaining anisotropic one-way speed merely by requiring that the speeds of light v1 and v2 in the two opposite directions of travel (out and back) satisfy the relation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In other words, a linear round-trip measurement of light speed will yield the constant c in every direction provided only that the harmonic mean of the one-way speeds in opposite directions always equals c. This is easily accomplished by defining the one-way velocity v1 as a function of direction arbitrarily for all directions in one hemisphere, and then setting the velocities in the opposite directions to v2 = cv1 / (2v1 − c). However, we also wish to cover more complicated round-trips, rather than just back and forth on a single line. To ensure that a circuit of light around an equilateral triangle with edges of length L yields a round-trip speed of c, the speeds v1, v2, v3 in the three equally spaced directions must satisfy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

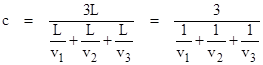

so again we see that the light speeds must have a harmonic mean of c. In general, to ensure that every closed loop of light, regardless of the path, yields the average speed c, it's necessary (and also sufficient) to have light speed v = C(θ) as a function of angle θ in a principal plane such that, for any positive integer n, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In units with c = 1, we need the n terms on the left side to sum to n, so the velocity function must be such that 1/C(θ) = 1 + f(θ) where the function f(θ) satisfies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

for all θ. The canonical example of such a function is simply f(θ) = k cos(θ) for any constant k. Thus if the speed of light varies as a function of the angle of travel θ relative to some primary axis according to the equation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

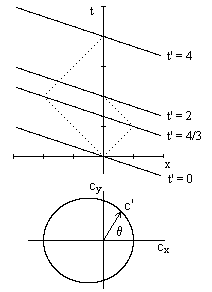

then all closed-loop measurements of the speed of light will yield the constant c, despite the fact that the one-way speed of light is distinctly non-isotropic for non-zero k. This equation describes an ellipse. If the speed of light is of this form (a proposition with non-trivial empirical content), the result of any measurement of the speed of light is independent of k. In this sense the value of k is strictly a matter of convention. If we choose to believe that light has the same speed in all directions, then we assume k = 0, and in order to send a synchronizing signal to two points we would locate ourselves midway between them (i.e., at the location where round trips between ourselves and those two points take the same amount of time.) On the other hand, if we choose to believe light travels twice as fast in one direction as in the other, then we would assume k = 1/3, and we would locate ourselves 2/3 of the way between them (i.e., twice as far from one as the other, so round trip times are two to one). The latter case is illustrated in the figure below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Regardless of what value we assume for k (in the range from −1 to +1), we can synchronize all clocks according to our belief, and everything will be perfectly consistent and coherent. Of course, in any case it's necessary to account consistently for the lapse of time for information to get from one clock to another, but the lapse of time between any two clocks separated by a distance L can be anything we choose in the range from virtually 0 to 2L/c. The only real constraint is that the speed be an ellipse function of the direction angle. |

|

|

|

The velocity profile given by (1) is simply the polar equation of an ellipse (or ellipsoid if revolved about the major axis), with the pole at one focus, the semi-latus rectum equal to c, and eccentricity equal to k. This just projects the ellipse given by cutting the light cone with an oblique plane. Interestingly, there are really two light cones that intersect on this plane, and they are the light cones of the two events whose projections are the two foci of the ellipse − for timelike separated events. Recall that all rays emanating from one focus of an ordinary ellipse and reflecting off the ellipse will re-converge on the other focus, and that this kind of ray optics is time-symmetrical. In this context our projective ellipse is the intersection of two null-cones, i.e., it is the locus of all points in spacetime that are null-separated from both of the "foci events". This was to be expected in view of the time-symmetry of Maxwell's equations (not to mention the relativistic Schrodinger equation), as discussed in Section 9. |

|

|

|

Our main reason for assuming k = 0 is our preference for symmetry, simplicity, and consistency with inertial isotropy. Within our empirical constraints, k can be interpreted as having any value between −1 and +1, but the principle of sufficient reason suggests that it should not be assigned a non-zero value in the absence of any rational justification. Nevertheless, it remains a convention (albeit a compelling one), but we should be clear about what precisely is – and what is not – conventional. The invariance of lightspeed is a convention, but the invariance of lightspeed in terms of inertial coordinates is an empirical fact, and this empirical fact is not a formal tautology, because inertial coordinates are determined by the mechanical inertia of material objects, independent of the propagation of light. |

|

|

|

Recall that Einstein’s 1905 paper states that if a pulse of light is emitted from an unaccelerated clock at time t1, and is reflected off some distant object at time t2, and is received back at the original clock at time t3, then the inertial coordinate synchronization is characterized by the relation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reichenbach noted that this is just one of a family of formally viable simultaneity conventions corresponding to the relation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where ε is any constant in the range from 0 to 1. Combined with the empirical fact that the round-trip speed of light is invariant, this leads to the same class of “elliptical speed” conventions discussed above, with ε = (k+1)/2 where k ranges from −1 to +1. For any inertial coordinates xI,tI, in terms of which the equations of Newtonian mechanics hold good (at least quasi-statically), we have ε = 1/2 and k = 0 by definition. Now, we can define a new system of coordinates xG,tG by applying a Galilean transformation xG = xI – vtI and tG = tI for some speed v ≠ 0, but the equations of Newtonian mechanics are not even quasi-statically valid in terms of these coordinates (without the introduction of fictitious forces), and the round trip speed of light is not invariant in terms of these coordinates. To remedy the latter, we can apply length contraction and time dilation to give the re-scaled coordinates xS = γxG and tS = γ−1tG where γ = [1−(v2/c2)]−1/2. This leads to the class of coordinate systems described above, with non-inertial synchronizations corresponding to k = v/c and ε = (1 + v/c)/2. In terms of these coordinates the two-way speed of light is invariant, and the one-way speed is given by equation (1), but mechanical inertia is still not isotropic in terms of these coordinates, so they are not inertial coordinates. |

|

|

|

To establish the inertial coordinate system xIʹ,tIʹ moving with speed v relative to the original inertial coordinates xI,tI we must apply the time skew transformation xI′ = xS, tI′ = tS − vxS/c2. This gives the full Lorentz transformation between inertial coordinate systems moving with the speed v relative to each other. |

|

|

|

Conversely, if we begin with the inertial rest frame coordinates for the primed frame (which Lorentz and Einstein agree are related to the putative absolute rest frame coordinate by a Lorentz transformation), and then apply the inverse time skew transformation, we arrive at the scaled Galilean coordinates. Needless to say, our choice of coordinates doesn’t affect the phenomena, it merely affects the terms of description. For example, by the inertial convention the speed of light is isotropic in terms of the rest frame coordinates of any material object, whereas by the Lorentzian convention it is not. Lorentz prefers coordinates with a common time foliation, rather than inertial coordinates. Thus the difference is simply due to different definitions of “rest frame coordinates”. If we specify inertial coordinate systems (i.e., coordinates in terms of which inertia is isotropic and Newton’s laws are quasi-statically valid) then there is no ambiguity. The speed of light is empirically isotropic in terms of every inertial coordinate system. |

|

|

|

In later sections we’ll see that the standard formalism of general relativity provides a convenient means of expressing the relations between spacetime events with respect to a larger class of coordinate systems, so it may appear that inertial references are less significant in the general theory. In fact, Einstein once hoped that the general theory would not rely on the principle of inertia as a primitive element. However, this hope was not fulfilled, and the underlying physical basis of the spacetime manifold in general relativity remains the set of primitive inertial paths (geodesics) through spacetime. Not only do these inertial paths determine the equivalence class of allowable coordinate systems (up to diffeomorphism), it even remains true that at each event we can construct a (local) system of inertial coordinates with respect to which the speed of light is c in all directions. Thus the empirical fact of lightspeed invariance and isotropy with respect to inertial coordinates remains as a primitive component of the theory. The difference is that in the general theory the convention of using inertial coordinates is less prevalent, because in general there is no single global inertial coordinate system, and non-inertial coordinate systems are often more convenient on a curved manifold. |

|

|