|

2.4 Doppler Shift for Sound and Light |

|

I was much further out than you thought |

|

And not waving but drowning. |

|

Stevie Smith, 1957 |

|

For historical reasons some older text books present two different versions of the Doppler shift equations, one for acoustic phenomena based on traditional Newtonian kinematics, and another for optical and electromagnetic phenomena based on relativistic kinematics. This may give the impression that different kinematics apply to the propagation of sound than to the propagation of light, but that is not the case. The kinematics of special relativity apply equally to the propagation of all kinds of signals. The traditional acoustic formulas are inexact, based on Newtonian approximations, but, when expressed exactly, they are perfectly consistent with the relativistic formulas. |

|

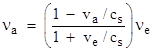

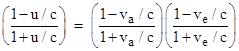

Consider a frame of reference in which the medium of signal propagation is assumed to be at rest, and suppose an emitter and absorber are located on the x axis, with the emitter moving to the left at a speed of ve and the absorber moving to the right, directly away from the emitter, at a speed of va. Let cs denote the speed at which the signal propagates with respect to the medium. Then, according to the classical (non-relativistic) treatment, the Doppler frequency shift is |

|

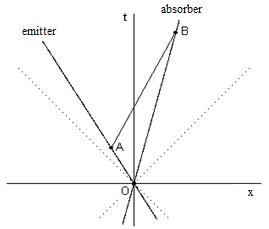

(It's assumed here that va and ve are less than cs, because otherwise there may be shock waves and/or lack of communication between transmitter and receiver, in which case the Doppler effect does not apply.) The above formula is often quoted as the Doppler effect for sound, and then another formula is given for light, suggesting that relativity arbitrarily treats sound and light signals differently. In truth, relativity has just a single formula for the Doppler shift, which applies equally to both sound and light. It can be read directly off the spacetime diagram shown below: |

|

|

|

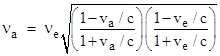

If an emitter on worldline OA turns a signal ON at event O and OFF at event A, the proper duration of the signal is the magnitude of OA, and if the signal propagates with the speed of the worldline AB, then the proper duration of the pulse for a receiver on OB will equal the magnitude of OB. Thus we have |

|

|

|

and |

|

|

|

|

|

Substituting xA = -vetA and xB = vatB into the equation for cs and re-arranging terms gives |

|

|

|

from which we get |

|

|

|

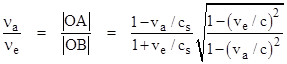

Substituting this into the ratio of |OA| / |OB| gives the ratio of proper times for the signal, which is the inverse of the ratio of frequencies: |

|

|

|

Now, if va and ve are both small compared to c, it's clear that the square root quantity will be indistinguishable from unity, and we can simply use the leading factor, which is formally identical to the classical Doppler formula for both sound and light. (The identity is only formal because the velocities here satisfy the relativistic composition law). However, if va and/or ve are fairly large (i.e., on the same order as c) and unequal we can't neglect the square root factor. |

|

It may seem surprising that the formula for sound waves in a fixed medium with absolute speeds for the emitter and absorber is also applicable to light, but notice that as the signal propagation speed cs goes to c, the above Doppler formula smoothly evolves into |

|

|

|

We recognize the quantity inside the square root as the multiplicative form of the relativistic composition law for velocities (discussed in Section 1.8). In other words, letting u denote the composition of the speeds va and ve given by the formula |

|

|

|

it follows that |

|

|

|

Consequently, as cs increases to c, the absolute speeds ve and va of the emitter and absorber relative to the fixed medium merge into a single relative speed u between the emitter and absorber, independent of any reference to a fixed medium, and we arrive at the relativistic Doppler formula for waves propagating at c for an emitter and absorber with a relative velocity of u: |

|

|

|

To clarify the relation between the classical and relativistic Doppler shift equations, recall that for a classical treatment of a wave with characteristic speed cs in a material medium the Doppler frequency shift depends on whether the emitter or the absorber is moving relative to the fixed medium. If the absorber is stationary and the emitter is receding at a speed of v (normalized so cs = 1), then the frequency shift is given by |

|

|

|

whereas if the emitter is stationary and the absorber is receding the frequency shift is |

|

|

|

To the first order these are the same, but they obviously differ significantly if v is close to 1. In contrast, the relativistic Doppler shift for light, with cs = c, does not distinguish between emitter and absorber motion, but simply predicts a frequency shift equal to the geometric mean of the two classical formulas, i.e., |

|

|

|

Naturally to first order this is the same as the classical Doppler formulas, but it differs from both of them in the second order, so we should be able to check for this difference, provided we can arrange for emitters and/or absorbers to be moving with significant speeds. The Doppler effect has in fact been tested at speeds high enough to distinguish between these two formulas. The possibility of such a test, based on observing the Doppler shift for “canal rays” emitted from high-speed ions, had been considered by Stark in 1906, and Einstein published a short paper in 1907 deriving the relativistic prediction for such an experiment. However, it wasn’t until 1938 that the experiment was actually performed with enough precision to discern the second order effect. |

|

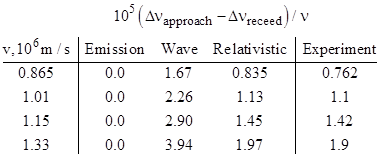

In that year, Ives and Stilwell shot hydrogen atoms down a tube, with velocity v (relative to the lab) ranging from about 0.8 to 1.3 times 106 m/sec. As the hydrogen atoms were in flight they emitted light in all directions. Looking into the end of the tube (with the atoms directly coming toward them), Ives and Stilwell measured a prominent characteristic spectral line in the light coming directly forward from the hydrogen. This characteristic frequency ν0 was blue-shifted up to the frequency ν1 in the lab frame as viewed from the front. They also placed a mirror at the opposite end of the tube, behind the hydrogen atoms, so they could look at the same light from behind, i.e., as the source was effectively moving away from them, red-shifted down to the frequency ν2. (They could just as well have placed another spectrometer at the back of the tube and dispensed with the mirror.) Assuming the lab is at rest in the aether, the classical wave theory predicts (to second order) |

|

|

|

whereas according to special relativity we have |

|

|

|

For completeness, we note that Ritz’s “emission” theory (or a classical wave theory in which the emitting atom is at rest in the ether) would have ν1 = ν0(1+v) and ν2 = ν0(1–v). Defining the quantities Δνapproach = ν1 – ν0 and Δνreceed = ν0 – ν2, it follows that, to the second order, the quantity (Δνapproach – Δνreceed)/ν0 equals 2v2 for the classical wave theory, 0 for a classical emission theory, and v2 for special relativity. The table below shows results from the original 1938 experiment for four different velocities of the hydrogen atom: |

|

|

|

Ironically, although the results of his experiment brilliantly confirmed Einstein’s prediction based on the special theory of relativity, Ives was not an advocate of relativity, and preferred a neo-Lorentzian interpretation of the phenomena. This illustrates that the results of an experiment can never uniquely identify the explanation. They can only split the range of available models into two groups, those that are consistent with the results and those that aren't. In this case we find that any model yielding the classical wave (or emission) theory prediction is ruled out, while the Lorentz/Einstein model is consistent with the observed results. |

|

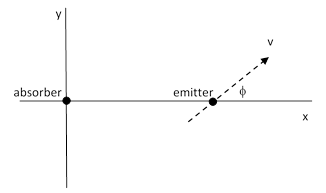

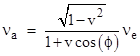

All the above was based on the assumption that the emitter and absorber are moving relative to each other directly along their "line of sight". More generally, we can give the Doppler shift for the case when the (inertial) motions of the emitter and absorber are at any specified angles relative to the "line of sight". Without loss of generality we can assume the absorber is stationary at the origin of inertial coordinates and the emitter is moving at a speed v and at an angle ϕ relative to the direct line of sight, as illustrated below. |

|

|

|

For two pulses of light emitted at coordinate times differing by Δte, arrival times at the receiver will differ by Δta = (1 + vr) Δt where vr = v cos(ϕ) is the radial component of the emitter’s velocity. Also, the proper time interval along the emitter’s worldline between the two emissions is Δτe = Δte (1 – v2)1/2. Therefore, since the frequency of the transmissions with respect to the emitter’s rest frame is proportional to 1/Δτe, and the frequency of receptions with respect to the absorber’s rest frame is proportional to 1/Δta, the full frequency shift is |

|

|

|

This differs in appearance from the Doppler shift equation given in Einstein’s 1905 paper, but only because, in Einstein’s equation, the angle ϕ is evaluated with respect to the emitter’s rest frame, whereas in our equation the angle is evaluated with respect to the absorber’s rest frame. These two angles differ because of the effect of aberration. If we let ϕ′ denote the angle with respect to the emitter's rest frame, then ϕ′ is related to ϕ by the aberration equation |

|

|

|

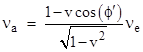

(See Section 2.5 for a derivation of this expression.) Substituting for cos(ϕ) into the previous equation gives Einstein’s equation for the Doppler shift, i.e., |

|

|

|

Naturally for the "linear" cases, when ϕ = ϕ′ = 0 or ϕ = ϕ′ = π we have |

|

|

|

respectively. This highlights the symmetry between emitter and absorber that is so characteristic of relativistic physics. |

|

Even more generally, consider an emitter moving with velocity u at the time of emission, an absorber moving with velocity v at the time of reception, and a signal propagating with velocity C, all in terms of an inertial coordinate system in which the signal’s speed |C| is independent of direction. This would apply to a system of coordinates at rest with respect to the medium of the signal, and it would apply to any inertial coordinate system if the signal is light in a vacuum. (It would also apply to the case of a signal emitted at a fixed speed relative to the emitter, but only if we take u = 0, because in this case the speed of the signal is independent of direction only in terms of the rest frame of the emitter.) We immediately have the relation |

|

|

|

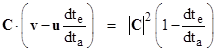

where re and ra are the position vectors of the emission and absorption events at the times te and ta respectively. Differentiating both sides with respect to ta and dividing through by 2(ta - te), and noting that (ra – re)/(ta – te) = C, we get |

|

|

|

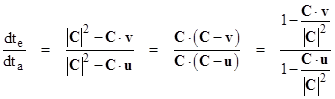

where u and v are the velocity vectors of the emitter and absorber respectively. Solving for the ratio dte/dta, we arrive at the relation |

|

|

|

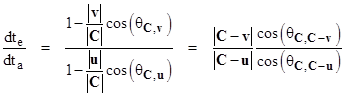

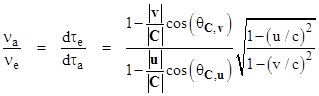

Making use of the dot product identity g∙h = |g||h|cos(θg,h) where θg,h is the angle between arbitrary vectors g and h (with respect to the reference coordinate system), these can be re-written as |

|

|

|

The frequency of any process is inversely proportional to the duration of the period, so the frequency at the absorber relative to the emitter, projected by means of the signal, is given by νa/νe = dte/dta. Therefore, the above expressions are formally the same as the classical Doppler effect for arbitrarily moving emitter and receiver (with the caveat that the velocities satisfy the relativistic composition law). However, the elapsed proper time along a worldline moving with speed v in terms of any given inertial coordinate system differs from the elapsed coordinate time by the factor |

|

|

|

where c is the speed of light in vacuum. Consequently, the actual ratio of proper times – and therefore proper frequencies – for the emitter and absorber is |

|

|

|

The leading ratio has the familiar form of the classical Doppler effect, and the square root factor is a purely relativistic correction. If we interpret the angles relative to the rest frame of the emitter (at the instant of emission) we must put u = 0, resulting in Einstein’s 1905 formula, whereas if we interpret the angles relative to the rest frame of the absorber (at the instant of reception) we must put v = 0, giving the alternative version as discussed previously. |

|

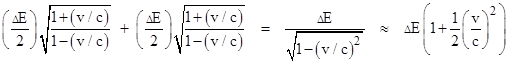

One interesting consequence of the relativistic Doppler effect is due to the fact that, as shown by Einstein in 1905, the energy of a pulse of light remains proportional to the frequency under transformations from one system of inertial coordinates to another. Hence if we are approaching a source of light, the energy of a given pulse of light (relative to our rest frame) from that source is greater than if we were receding from the source, and the ratio of energies for these two cases is exactly proportional to the ratio of frequencies. (This is consistent both with Maxwell’s equations and with the quantum relation E = hn.) Now, consider a stationary object that emits two equal pulses of light in opposite directions, and then consider the amount of energy carried away by these pulses with respect to a coordinate system moving with speed v along the axis of the pulses. Classically the frequency (and hence the energy) of the forward-going pulse would be Doppler shifted by the factor 1 + v, and the backward-going pulse would be shifted by the factor 1 – v, so if each pulse carried energy ΔE/2 relative to the original stationary coordinates, for a total energy of ΔE, the energy emitted relative to the moving coordinates would be (ΔE/2)(1 + v) + (ΔE/2)(1 – v) = ΔE. Thus the energy emitted is the same. However, using the relativistic formula, the total emitted energy with respect to the moving coordinates is |

|

|

|

Thus the combined energy content of the emitted pulses is (for small v) slightly greater with respect to the moving coordinates than with respect to the stationary coordinates. Relative to the stationary coordinates, let E denote the total energy of the object prior to the emissions, and define the parameter m1 such that the total energy of the object increases by (1/2)m1v2 for an incremental velocity v. In these terms, the total energy of the object prior to the emissions is E relative to the stationary coordinates, and E + (1/2)m1v2 relative to a system of coordinates moving (along the axis of the pulses) with an incremental speed v. |

|

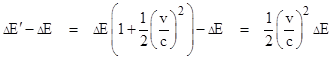

Following the emission of the pulses the total energy of the object is E – ΔE relative to the stationary coordinates, (the object remains stationary by symmetry, because the pulses are equal and opposite), and we can define a parameter m2 such that the total energy of the object increases by (1/2)m2v2 for an incremental velocity v. Thus the total energy of the object following the emissions is E – ΔE + (1/2)m2v2 relative to the moving system. Therefore, the change in energy of the object relative to the moving system of coordinates, which must equal the energy ΔEʹ of the pulses relative to the moving coordinates, is |

|

|

|

This implies that |

|

|

|

Using the classical Doppler formula we have ΔEʹ – ΔE = 0, and so m1 = m2, which signifies that the constant of proportionality “m” (usually called “rest mass”) between v2 and the change in E for incremental values of v is unaffected by the emission of the light pulses. However, the relativistic Doppler effect for two oppositely-directed pulses with incremental v gives (as noted above) |

|

|

|

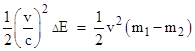

Therefore we have |

|

|

|

and so |

|

|

|

which signifies that the “rest mass” of the object has been reduced by the amount ΔE/c2 due to the emission of energy ΔE. This is the argument that Einstein gave in his 1905 paper entitled “Does the Inertia of a Body Depend on its Energy Content?”. It’s noteworthy that the equivalence of mass and energy relies crucially on the relativistic, as opposed to the classical, Doppler shift. |

|

|