|

No Four Squares In Arithmetic Progression |

|

|

|

To prove that four consecutive terms in an arithmetic sequence cannot all be squares, suppose there exist four squares A2, B2, C2, D2 in increasing arithmetic progression, i.e., we have B2–A2 = C2–B2 = D2–C2. We can assume the squares are mutually co-prime, and the parity of the equation shows that each square must be odd. Hence we have co-prime integers u,v such that A = u–v, C = u+v, u2+v2 = B2, and the common difference of the progression is (C2–A2)/2 = 2uv. |

|

|

|

We also have D2 – B2 = 4uv, which factors as [(D+B)/2][(D–B)/2] = uv. The two factors on the left are co-prime, as are u and v, so there exist four mutually co-prime integers a,b,c,d (exactly one even) such that u = ab, v = cd, D+B = 2ac, and D–B = 2bd. This implies B = ac–bd, so we can substitute into the equation u2+v2 = B2 to give (ab)2+(cd)2 = (ac–bd)2. This quadratic is symmetrical in the four variables, so we can assume c is even and a, b, d are odd. From this quadratic equation we find that c is a rational function of the square root of a4–a2d2+d4, which implies there is an odd integer m such that a4–a2d2+d4 = m2. |

|

|

|

Since a and d are odd there exist co-prime integers x and y such that a2 = k(x+y) and d2 = k(x–y), where k = ±1. Substituting into the above quartic gives x2+3y2 = m2, from which it's clear that y must be even and x odd. Changing the sign of x if necessary to make m+x divisible by 3, we have 3(y/2)2 = [(m+x)/2][(m–x)/2], which implies that (m+x)/2 is three times a square, and (m-x)/2 is a square. Thus we have co-prime integers r and s (one odd and one even) such that (m+x)/2 = 3r2, (m-x)/2 = s2, m = 3r2+s2, x = 3r2–s2, and y = ±2rs. |

|

|

|

Substituting for x and y back into the expressions for a2 and d2 (and transposing if necessary) gives a2 = k(s+r)(s–3r) and d2 = k(s-r)(s+3r). Since the right hand factors are co-prime, it follows that the four quantities (s–3r), (s–r), (s+r), (s+3r) must each have square absolute values, with a common difference of 2r. These quantities must all have the same sign, because otherwise the sum of two odd squares would equal the difference of two odd squares, i.e., 1+1 = 1–1 (mod 4), which is false. |

|

|

|

Therefore, we must have |3r| < s, so from m = 3r2 + s2 we have 12r2 < m. Also the quartic equation implies m < a2 + d2, so we have the inequality |2r| < |SQRT(2/3)max(a,d)|. Thus we have four squares in arithmetic progression with the common difference |2r| < |2abcd|, the latter being the common difference of the original four squares. This contradicts the fact that there must be a smallest absolute common difference for four squares in arithmetic progression, so the proof is complete.□ |

|

|

|

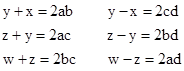

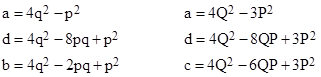

Incidentally, Fermat proposed this problem in a letter to Frenicle in 1640, and later claimed to have a proof, although as usual he never shared it with anyone. Weil says that Euler published (posthumously) a proof in 1780, but “it is somewhat confusedly written, obviously by his assistants, at a time when he was totally blind”. Weil then says a better proof was given by J. Itard in 1973, but provides no description. Dickson's "History of the Theory of Numbers" describes a alleged proof (attributed to Bronwin and Furnass) of this proposition, but the “proof” is incomplete at best. The equality of the differences y2–x2, z2–y2 , and w2–z2 is said to imply the existence of four integers a,b,c,d such that |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

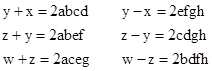

but no justification for this assertion is given. It is certaintly true that, if w,x,y,z are all odd, then there exist eight integers a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h such that |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

but Dickson offers no justification for how the eight integers can be reduced to just four, so the proof given there can’t be considered complete. The inadequacy of that proof was mentioned on an internet newsgroup in 1994, and no one knew of any elementary published alternative, so this led me to devise and post the proof given above. (As an aside, in 2007 a noted mathematician found the above proof on my web site, and wrote a paper in which he just copied it and claimed it as his own – omitting any mention of the actual source. After seeing his paper I emailed him, asking if he’d seen my web page before writing his paper, and he surprisingly admitted that he had, but said that, since it was not officially published, he had felt free to publish it himself.) |

|

|

|

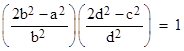

The “no arithmetic progression of four squares” theorem can be used to answer other questions as well. For example, are there rational numbers p, q other than unity such that (p2, q2) is a point on the hyperbola given by (2–x)(2–y) = 1? To see why the answer is no, suppose p = a/b and q = c/d (both fractions reduced to least terms). Then if (p2,q2) is on the hyperbola we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Since b2 is coprime to 2b2–a2 and c2 is coprime to 2d2–c2 it follows that b2 = 2d2–c2 and d2 = 2b2–a2. Rearranging terms we get b2–d2 = d2–c2 and d2–b2 = b2–a2. Together these equations imply that a2, b2, d2 and c2 are in airthmetic progression, which is impossible. |

|

|

|

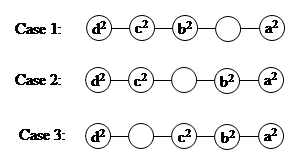

Another interesting question is whether four of five consecutive terms in arithmetic progression can be squares. The three possible cases to consider are depicted below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We can easily show that Case 2 has no solutions. The conditions for that case are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and these conditions imply |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

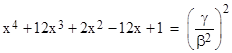

From the theory of quadratic forms we know the primitive solutions of these two individual equations are of the form |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

respectively for some integers p, q, P, Q. If either p or P are even, then all of the variables are even, so the solution is not primitive and we can divide each variable by 2 until p and P are both odd. It follows that these two equations have no simultaneous solution, because the variable a is one less than a multiple of 4 in the left-hand solution, whereas it is one greater than a multiple of four in the right-hand solution. |

|

|

|

Hence the only possibilities are Cases 1 and 3. It so happens that each of these has a solution. For Case 1 we have the solution a=23, b=17, c=13, d=7. This was found by Cunningham in 1906. (Dickson notes that this leads to an infinite set of solutions, and that Cunningham computed two much larger solutions, but doesn’t give them.) We also have the solution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

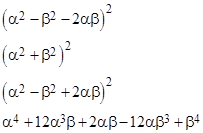

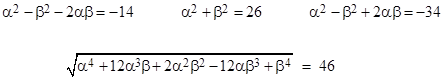

For Case 3 we have the solution a=4183, b=3637, c=2993, d=647. The two minimal solutions of the respective conditions are related to each other in a subtle way, as discussed in another note. The simplest way to approach this problem (i.e., Cases 1 and 3), is to begin with three squares in arithmetic progression, which can be written as (a–b)2, c2, and (a+b)2, with the condition that a2+b2 = c2. Using the primitive form of the Pythagorean solution a = α2–β2, ,b = 2αβ, c = α2+β2, we get the three squares in arithmetic progression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

with the common difference 4αβ(α–β)(α+β). Subtracting twice this value from the left-hand square gives the lowest value for a solution of Case 3, whereas adding to the right-hand term gives the highest value for a solution of Case 1. We must make this term equal to a square, so we require |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus Cases 1 and 3 are governed by the same Diophantine equation, the only difference being that in one case α,β have the same sign and in the other case they have opposite signs. One simple way of finding a solution is to write the equation as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hence we have a solution if we choose α,β to make the second two terms vanish, i.e., |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

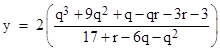

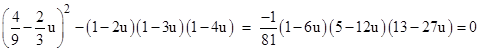

so we have the solution α = –2, β = 3. It’s clear by inspection that transposing α,β and negating one of their signs leaves the polynomial unchanged, so we also have the equivalent solution α = 3, β = 2. We can generate infinitely many more solutions using a method described by Euler. Divide through the original polynomial by β4, and let x denote the ratio α/β, so we seek a rational value of x that makes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

so the right hand side is an arbitrary rational square. We already know that x = 3/2 is a solution. Now suppose we have another solution q, and let us make the substitution x = y + q, which gives |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where r2 is the rational square given by the solution q. Repeating the previous method, we can write this in the form |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

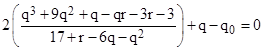

Choosing y so that the sum of the two right-hand terms vanishes, we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The corresponding value of x is given by adding q, so we have another solution x = q0, and hence we can write |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It follows that |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Squaring both sides and substituting for r2 the quantity q4+12q3+2q2–12q+1, we get the quadratic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

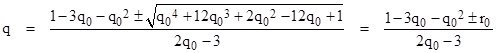

If q0 equals 3/2 or –2/3 this degenerates and the only non-zero root is q = 39/46 or –46/39 respectively. Thus from the smallest solution we get the next (known) larger one. For all other values of q0 we can solve the preceding quadratic for q to give |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

which yields two non-zero rational values of q such that |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

is also rational. One of these solutions is the “previous” ratio in the sequence (i.e., the ratio in smaller terms), and the other is the “next” ratio in the sequence (a ratio in larger terms). Hence given q0 and r0, we can compute q and r, and then repeat the process using these as the new values of q0 and r0. Beginning with q0 = 3/2 and r0 = 23/4 we get the sequence of q values |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and so on. Letting α and β denote respectively the numerator and denominator of q, the corresponding solution (progression of squares) is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

with the double interval between the third and fourth values, and this is either an increasing or decreasing sequence (corresponding to Case 1 or 3) depending on the sign of the quarter difference αβ(α–β)(α+β). |

|

|

|

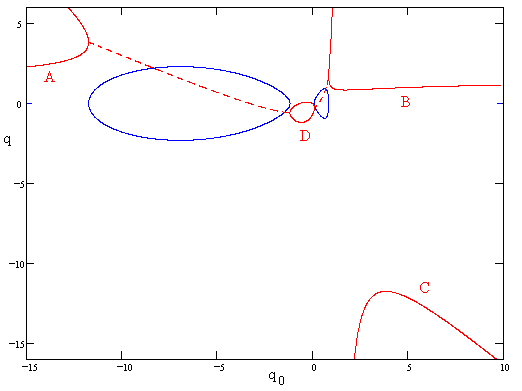

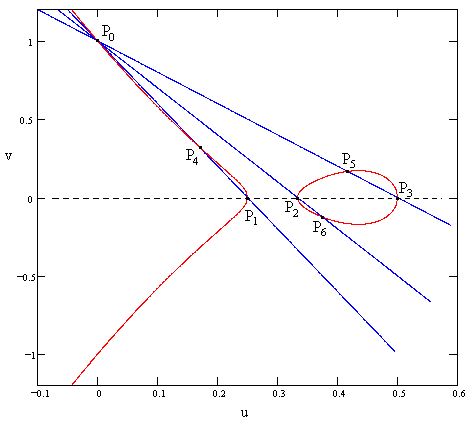

The sequence of q values beginning with 3/2 all lie on branches A, B, or C of the curve defined by equation (1) as plotted below. (The blue portion represents the imaginary part.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

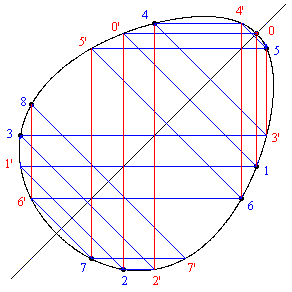

Alternatively, if we begin with the initial value –2/3, the sequence of values all lie on the closed locus D. In both cases, every point on the real locus is arbitrarily close to one of the iterates. An expanded plot of locus D, along with the first several iterates, is shown in the figure below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The point denoted by 0 is at the origin of the coordinates (i.e., q = q0 = 0), and from there we can proceed horizontally to the point 0’, then we can proceed perpendicularly to the q = q0 line to the point 1, then horizontally to the point 1’, and so on. In this way we pass through each of the infinitely-many rational points on the curve that are related to the “0” point by equation (1). |

|

|

|

This sequence of quadratic equations is perhaps the clearest method of generating solutions, but the problem can also be expressed in terms of elliptic curves. First, for convenience, we re-write equation (1) using the variables x and y in place of q0 and q. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Any rational point on this curve represents a solution of the original problem (four of five terms in arithmetic progression are squares), because if x is a rational number the value of y is rational if and only if the discriminant x4+12x3+2x2–12x+1 is a rational square, which is the necessary and sufficient condition for a solution of the original problem. Also, in that case, y too makes that polynomial a rational square. So we seek rational points on the above curve. If we define the variables |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

we can make the rational substitutions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

into the preceding equation to give the elliptic curve |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A plot of this locus is shown below. |

|

|

|

|

|

Given any two rational points on this curve, the line through those two points generally intersects the curve at a third point that must also be rational. This curve has the trivial rational points P0 = (0,±1), P1 = (1/2,0), P2 = (1/3,0), and P3 = (1/4,0). To find a new rational point, consider the line through P0 and P3, which has the equation v = 1–2u. Substituting this for v in equation (3) and simplifying, we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus the point P5 has the rational coordinates u = 5/12, v = 1/6, which corresponds to the values x = –1/5, y = –1, meaning that these values satisfy (2), and therefore both of them make the function x4+12x3+2x2–12x+1 a rational square. If we put x = α/β for co-prime integers α,β, then the rational value x = –1/5 corresponds to α = –1, β = 5, which gives the four values whose squares lie in five consecutive terms of an arithmetic progression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is twice the smallest non-trivial solution of Case 1, i.e., the numbers 7, 13, 17, 23. The rational points P6 = (3/8,–1/8) and P4 = (1/6,1/3) also map to this same solution. Now consider a line through points P4 and P5, having the equation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Substituting for v in equation (3) and simplifying, we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

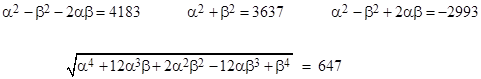

Thus the line through P4 and P5 strikes the curve again at u = 13/27, v = 10/81, which maps to the values x = –2/3, y = –46/39. The four squares corresponding to this x value are again just the smallest solution, but the squares corresponding to this y value, for which α = –46 and β = 39, are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is the smallest solution of Case 3. Continuing to consider the lines through other pairs of rational points, we can generate all the same solutions that were given by the previous “quadratic tree” method. |

|

|