|

4.3 Free-Fall Equations |

|

|

|

When, therefore, I observe a stone initially at rest falling from an elevated position and continually acquiring new increments of speed, why should I not believe that such increases take place in a manner which is exceedingly simple and rather obvious to everybody? |

|

Galileo Galilei, 1638 |

|

|

|

As noted in the previous chapter, according to Newtonian physics the spatial separation between two particles of combined mass m in radial gravitational free-fall (i.e., with no angular momentum) satisfies the relation |

|

|

|

|

|

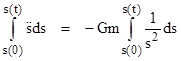

where dots signify derivatives with respect to time. We will find in Section 6 that, according to general relativity, the radial position of a test particle as a function of the particle’s proper time in a spherically symmetrical gravitational field satisfies an equation of the same form, so it’s interesting from both a Newtonian and a relativistic standpoint to derive the explicit solution of this equation. Integrating both sides over ds from an arbitrary initial separation s(0) to the separation s(t) at some other time t gives |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

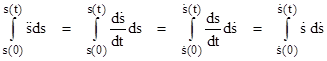

The left hand integral can be rewritten as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

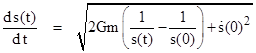

Therefore, the previous equation can easily be integrated to give |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

which shows that the quantity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

is

invariant for all t. Solving the equation for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

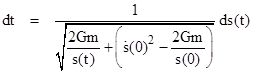

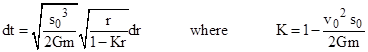

Rearranging this gives |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

To

simplify the expressions, we put s0 = s(0), v0 = |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

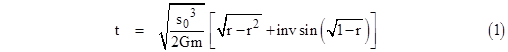

There are two cases to consider. If K is positive, then the trajectory is bounded, and there is some point on the trajectory (the apogee) at which v = 0. Choosing this point as our time origin t = 0, we have K=1, and the standard integral gives |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

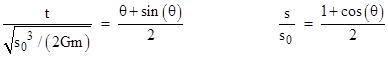

This equation describes a (scaled) cycloidal relation between t and r, which can be expressed parametrically in terms of a fictitious angle θ as follows |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

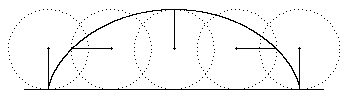

A cycloid is the curve traced by a point fixed on the perimeter of a wheel rolling along a flat surface, as illustrated in the figure below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

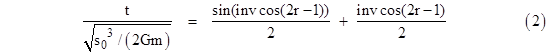

To verify that the two parametric equations are equivalent to (1), we can solve the second for θ and substitute into the first to give |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

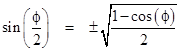

Using

the trigonometric identity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Also, letting ϕ = invcos(2r-1), we can use the trigonometric identity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

to show that this angle is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

so the second term on the right side of (2) is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

which completes the demonstration that the cycloid relation given by (2) is equivalent to the free-fall relation (1). |

|

|

|

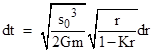

The second case is when K is negative. For this case we can conveniently express the equations in terms of the positive parameter k = -K. The standard integral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

tells us that, for any two points r0 and r1 on the trajectory, the time interval is related to the separations according to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

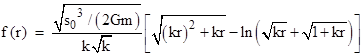

where |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notice that if we define S0 = s0 / k and R = kr, then this becomes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

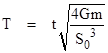

Thus, if we define the normalized time parameter |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

then the normalized equation of motion is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This

represents the shape of every non-rotating separation between two particles

of combined mass m for which k is positive, which means that the absolute

value of v0 exceeds |

|

|