|

2.3 The Inertia of Energy |

|

|

|

Please reveal who you are of such fearsome form... I wish to clearly know you, the primeval being, because I cannot fathom your intention. Lord Krishna said: I am terrible Time, destroyer of all beings in all worlds, here to destroy this world. Of those heroic soldiers now arrayed in the opposing army, even without you, none will be spared. |

|

Bhagavad Gita |

|

|

|

The fact that inertial coordinate systems are related by Lorentz transformations (rather than Galilean transformations) has very profound implications, because acceleration is not invariant under Lorentz transformations. As a result, the acceleration of an object subjected to a given force depends on the frame of reference. Since acceleration is a measure of the object’s inertia, this implies that the object’s “inertial mass” depends on the frame of reference. Now, the kinetic energy of an object also depends on the frame of reference, and we find that the variation of kinetic energy is always exactly c2 times the variation in inertial mass, where c is the speed of light. Thus the Lorentz covariance of the inertial measures of space and time implies that all forms of energy possess inertia, which in turn suggests that all inertia represents energy. |

|

|

|

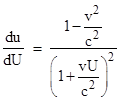

To show this quantitatively, let k denote a system of inertial coordinates and let K denote another such system, with spatially aligned axes, moving with speed v in the positive x direction relative to k. If a particle P is moving with speed U (in the same direction as v) relative to K, then the speed u of P relative to the original k coordinates is given by the composition law for parallel velocities (as derived at the end of Section 1.6) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Differentiating with respect to U gives |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

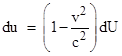

Hence, at the instant when P is momentarily co-moving with the K coordinates (i.e., when U = 0, so P is at rest in K, and u = v), we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

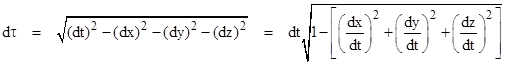

If

we let t and τ denote the time coordinates of k and K respectively, then

from the metric (dτ)2 = c2(dt)2 – (dx)2

and the fact that v2 = (dx/dt)2 along the worldline of

P at this moment, it follows that the incremental lapse of proper time

dτ along the worldline of P as it advances from t to t + dt is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

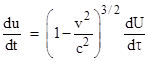

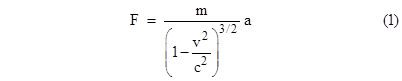

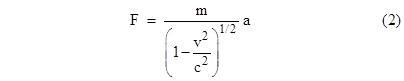

The quantity a = du/dt is the acceleration of P with respect to the k coordinates, whereas a0 = dU/dτ is the acceleration of P with respect to the K coordinates (relative to which it is momentarily at rest). Now, by symmetry, a force F exerted along the axis of motion between a particle at rest in k on an identical particle P at rest in K must be of equal and opposite magnitude with respect to both frames of reference. (This is consistent with the transformation of electromagnetic force derived at the end of Section 2.2.) Also, by definition, a force of magnitude F applied (adiabatically) to a particle of “rest mass” m will result in an acceleration a0 = F/m in terms of inertial coordinates in which the particle is momentarily at rest. Therefore, using the preceding relation between the accelerations with respect to the k and K coordinates, we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

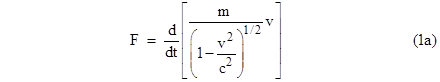

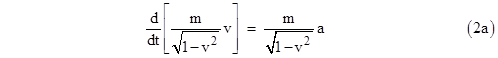

By analogy with the Newtonian equation F = ma, the coefficient of “a” in this expression is sometimes called the “longitudinal mass”, since it represents the ratio of force to acceleration along the direction of motion. However, in Newtonian mechanics, force is also equal to the time derivative of momentum p = mv, and we note that, since du/dt = dv/dt at constant U=0, equation (1) can be written as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

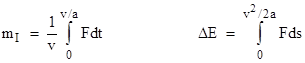

The coefficient of v inside the square brackets is the inertial mass mI (also called relativistic mass) of the particle relative to the system k. We will see below that this same quantity characterizes the transverse inertia. The quantity mIv in brackets represents the relativistic momentum of the particle, which we see is the integral of Fdt over an interval in which the particle is accelerated by a force F from rest to velocity v. We also know that the work done on the particle is the integral of Fds, and this is a reversible process, i.e., after we accelerate the particle by doing work on it, the particle can then do an equal amount of work on its surroundings and thereby be decelerated back to its initial state. Hence the integral of Fds from rest to velocity v is a state variable, and we will call it the kinetic energy, denoted by ΔE. |

|

|

|

For both mIv and ΔE the results of the integrations are independent of the pattern of acceleration, so to evaluate these variables for any given v we can assume constant acceleration “a” throughout the interval. Therefore the integral of Fdt is evaluated from t = 0 to t = v/a, and since s = (1/2)at2, the integral of Fds is evaluated from s = 0 to s = v2/(2a). It follows that the inertial mass and the kinetic energy of the particle at any speed v are given by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

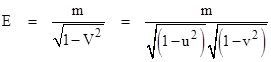

If

the force F were equal to ma (as in Newtonian mechanics) these two quantities

would equal m and (1/2)mv2 respectively. However, we’ve seen that

consistency with relativistic kinematics requires the force to be given by

equation (1). As a result, the inertial mass is given by mI = m/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The exact proportionality between the extra inertia and the extra energy of a moving particle naturally suggests that the energy itself has contributed the inertia, and this in turn suggests that all of the particle’s inertia (including that due to its rest mass m) corresponds to some form of energy according to the very general and important relation E = mc2. For this equivalence to be physically meaningful, we are led to the expectation that all inertial mass – even the rest mass of elementary particles - is potentially convertible to massless energy (i..e., energy with no rest mass). |

|

|

|

In 1905 the only experimental test that Einstein could imagine was to see if a lump of "radium salt" loses weight as it gives off radiation. In 1908 Rutherford showed that radium-226 actually emits helium nuclei (“alpha particles”) as it decays down to radon-222, so it would be necessary to account for both the rest mass and the kinetic energy of the emitted radiation. The same is true with a nuclear bomb, i.e., only binding energy of the nucleus is converted to kinetic energy, so it doesn't demonstrate an elementary massive particle being converted into energy. |

|

|

|

However, today we can observe electrons and positrons annihilating each other completely, and yielding amounts of energy precisely in accord with the predictions of special relativity. Moreover, the rest masses of the quarks comprising a proton is only 1% of the rest mass of the proton, the remainder being binding and kinetic energy, and even the rest masses of quarks and electrons is now known to be due to internal degrees of freedom of massless energy interacting with the Higgs field. Thus, as special relativity led us to anticipate, it appears that all rest mass is bound energy. |

|

|

|

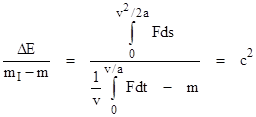

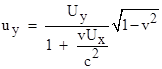

In the preceding discussion we focused on a particle subjected to a force parallel to the particle’s direction of motion. As noted, the symmetry of this situation ensures that the applied force in terms of the relatively moving coordinates equals the force in terms of the rest frame of the particle. A similar analysis can be performed for the application of a force perpendicular to the direction of motion of a particle, although in this case the force is not symmetrical with respect to the two frames. Indeed we saw in Section 2.2 that if an electromagnetic force in the rest frame of the particle is F0, then it is F = (1–v2)1/2 F0 in terms of the inertial coordinates in which the particle is moving with speed v in a direction perpendicular to the force. We also noted that all kinds of forces must transform in this same way, because otherwise the deviation from electromagnetic forces could be used to determine an absolute speed. So, analogously to the longitudinal case, we begin by writing the composition law for perpendicular velocities (see Section 1.8) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

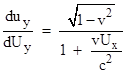

Differentiating with respect to Uy gives |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hence, at the instant when P is momentarily co-moving with the K coordinates (i.e., when Ux = Uy = 0, so P is at rest in K, and u = v), we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

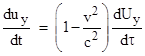

If

we again let t and τ denote the time coordinates of k and K

respectively, then from the metric (dτ)2 = c2(dt)2

– (dx)2 and the fact that v2 = (dx/dt)2 it

follows that the incremental lapse of proper time dτ along the worldline

of P as it advances from t to t + dt is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

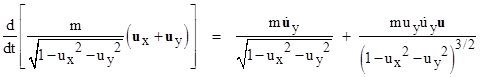

The quantity a = duy/dt is the acceleration of P with respect to the k coordinates, whereas a0 = dUy/dτ is the acceleration of P with respect to the K coordinates (relative to which it is momentarily at rest). Therefore, the equation F0 = ma0 becomes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where we have made use of the fact that forces perpendicular to the direction of motion transform according to F = (1–v2)1/2 F0 as discussed above. The coefficient of the acceleration “a” in this equation is sometimes called the “transverse mass”. Comparison with equation (1) shows that this differs from the “longitudinal mass”, so in general the ratio of force to acceleration is not a simple scalar. However, if we again evaluate the inertial mass, this time in the transverse direction, we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

At the instant when ux = v and uy = 0, this reduces to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

which is consistent with (2). So again we find that the inertial mass (i.e., the momentum divided by the velocity) is the same as in the longitudinal case, so inertial mass is a scalar, proportional to energy. It’s worth emphasizing that this works only because all forces transform in the same way as electromagnetic forces. |

|

|

|

The preceding discussion represents one of the historical lines of thought that led to a satisfactory basis for relativistic mechanics, but in hindsight the subject can be developed in a more efficient way. A typical modern approach begins with the definition of momentum as the product of rest mass and velocity. One formal motivation for this definition is that the resulting 3-vector is well-behaved under Lorentz transformations, in the sense that if this quantity is conserved with respect to one inertial frame, it is automatically conserved with respect to all inertial frames (which would not be true if we defined momentum in terms of, say, longitudinal mass). Naturally this definition also agrees with non-relativistic momentum in the limit of low velocities. (The heuristic technique of deducing the appropriate observable parameters of a theory from the requirement that they match classical observables in the classical limit was used extensively in early development of relativity, and later served the same purpose in the development of quantum mechanics, where it is known as the "Correspondence Principle".) |

|

|

|

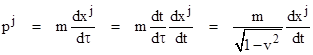

Based on this definition, the modern approach then simply postulates that momentum is conserved, and defines relativistic force as the rate of change of momentum with respect to the proper time of the object. This is essentially Newton's Second Law, motivated largely by the fact that this definition of "force", together with conservation of momentum, implies Newton's Third Law (at least in the case of contact forces). However, from a purely relativistic standpoint, the definition of momentum as a 3-vector seems incomplete. Its three components are proportional to the derivatives of the three spatial coordinates x,y,z of the object with respect to the coordinate time of the object (which is proper time at rest), but what about the derivative of the temporal coordinate? If we let xj, j = 0, 1, 2, 3 denote the coordinates t,x,y,z, then it seems natural to consider the 4-vector |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We then define the relativistic force 4-vector as the proper rate of change of momentum, i.e., |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Our correspondence principle easily enables us to associate the three components p1, p2, p3 with our original momentum 3-vector (scaled by (1–v2)–1/2), but now we have an additional component, p0, equal to m(dt/dτ), which we will find corresponds to the total "energy" E of the object. In full four-dimensional spacetime, the coordinate time t is related to the object's proper time τ according to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In geometric units (c = 1) the quantity in the square brackets is just v2. Substituting back into our energy definition, we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notice that this is identical to what we previously called the inertial mass, but now we see that it represents the total energy of the particle. The first term on the right side is simply m (or mc2 in normal units), so we interpret this as the rest energy (and also the rest mass) of the object. This is sometimes presented as a derivation of mass-energy equivalence, but at best it's really just a suggestive heuristic argument. The key step in this "derivation" was when we blithely decided to call p0 the total "energy" of the object. Strictly speaking, we violated our "correspondence principle" by making this definition, because by correspondence with the low-velocity limit, the energy E of a particle should be something like (1/2)mv2, and clearly p0 does not reduce to this in the low-speed limit. Nevertheless, we defined p0 as the total "energy" E, and since that component equals m when v = 0, we essentially just defined our result E = m (or E = mc2 in ordinary units) for a mass at rest. From this reasoning it isn't clear that this is anything more than a bookkeeping convention, one that could just as well be applied in classical mechanics using some arbitrary squared velocity to convert from units of mass to units of energy. The assertion of physical equivalence between inertial mass and energy has more than formal significance only because, as discussed above, it is actually possible for the entire mass of an object, including its rest mass, to be released as massless energy. |

|

|

|

As mentioned above, even the fact that nuclear reactors give off huge amounts of energy does not really substantiate the complete equivalence of energy and inertial mass, because the energy given off in such reactions represents just the binding energy holding the nucleons (protons and neutrons) together. The binding energy is the amount of energy required to pull a nucleus apart. (The terminology is slightly inapt, because a configuration with high binding energy is actually a low energy configuration, and vice versa.) Of course, protons are all positively charged, so they repel each other by the Coulomb force, but at very small distances the strong nuclear force binds them together. Since each nucleon is attracted to every other nucleon, we might expect the total binding energy of a nucleus comprised of N nucleons to be proportional to N(N-1)/2, which would imply that the binding energy per nucleon would increase linearly with N. However, saturation effects cause the binding energy per nucleon to reach a maximum for nuclei with N » 60 (e.g., iron), then to decrease slightly as N increases further. As a result, if an atom with (say) N = 230 is split into two atoms, each with N=115, the total binding energy per nucleon is increased, which means the resulting configuration is in a lower energy state than the original configuration. In such circumstances the two small atoms have slightly less total rest mass than the original large atom, but at the instant of the split the overall "mass-like" quality is conserved, because those two smaller atoms have enormous velocities, precisely such that the total relativistic mass is conserved. (This physical conservation is the main reason the old concept of relativistic mass has never been completely discarded.) If we then slow down those two smaller atoms by absorbing their energy, we end up with two atoms at rest, at which point a little bit of apparent rest mass has disappeared from the universe. On the other hand, it is also possible to fuse two light nuclei (e.g., N = 2) together to give a larger atom with more binding energy, in which case the rest mass of the resulting atom is less than the combined rest masses of the two original atoms. In either case (fission or fusion), a net reduction in rest mass occurs, accompanied by the appearance of an equivalent amount of kinetic energy and radiation. (The actual detailed mechanism by which binding energy, originally a "rest property" with isotropic inertia, becomes a kinetic property representing what we may call relativistic mass with anisotropic inertia, is not well understood.) |

|

|

|

It may appear that equation (3) fails to account for the energy of light, because it gives E proportional to the rest mass m, which is zero for a photon. However, the denominator of (3) is also zero for a photon (because v = 1), so we need to evaluate the expression in the limit as m goes to zero and v goes to 1. We know from the study of electro-magnetic radiation that although a photon has no rest mass, it does (according to Maxwell's equations) have momentum, equal to |p| = E (or E/c in conventional units). This suggests that we try to isolate the momentum component from the rest mass component of the energy. To do this, we square equation (3) and expand the simple geometric series as follows |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Excluding the first term, which is purely rest mass, all the remaining terms are divisible by (mv)2, so we can write this as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The right-most term is simply the squared magnitude of the momentum, so we have the apparently fundamental relation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

consistent with our premise that the energy E (or E/c in conventional units) equals the magnitude of the momentum |p| for a photon. Of course, electromagnetic waves are classically regarded as linear, meaning that photons don't ordinarily interfere with each other (directly). As Dirac said, "each photon interferes only with itself... interference between two different photons never occurs". However, the non-linear field equations of general relativity enable photons to interact gravitationally with each other. Wheeler coined the word "geon" to denote a swarm of massless particles bound together by the gravitational field associated with their energy, although he noted that such a configuration would be inherently unstable, viz., it would very rapidly either dissipate or shrink into complete gravitational collapse. Also, it's not clear that any physically realistic situation would lead to such a configuration in the first place, since it would require concentrating an amount of electromagnetic energy equivalent to the mass m within a radius of about r = Gm/c2. For example, to make a geon from the energy equivalent of one electron, it would be necessary to concentrate that energy within a radius of about (6.7)10–58 meters. |

|

|

|

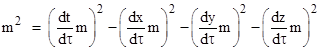

An interesting alternative approach to deducing (4) is based directly on the Minkowski metric |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is applicable both to massive timelike particles and to light. In the case of light we know that the proper time dτ and the rest mass m are both zero, but we may postulate that the ratio m/dτ remains meaningful even when m and dτ individually vanish. Multiplying both sides of the Minkowski line element by the square of this ratio gives immediately |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first term on the right side is E2 and the remaining three terms are px2, py2, and pz2, so this equation can be written as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

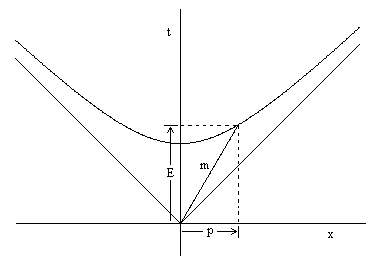

Hence this expression is nothing but the Minkowski spacetime metric multiplied through by (m/dτ)2, as illustrated in the figure below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The kinetic energy of the particle with rest mass m along the indicated worldline is represented in this figure by the portion of the total energy E in excess of the rest energy. |

|

|

|

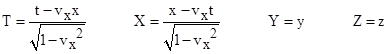

Returning to the question of how mass and energy can be regarded as different expressions of the same thing, recall that the energy of a particle with rest mass m and speed V is m/(1–V2)1/2. We can also determine the energy of a particle whose motion is defined as the composition of two orthogonal speeds. Let t,x,y,z denote the inertial coordinates of system S, and let T,X,Y,Z denote the (aligned) inertial coordinates of system S′. In S the particle is moving with speed vy in the positive y direction so its coordinates are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Lorentz transformation for a coordinate system S′ whose spatial origin is moving with the speed v in the positive x (and X) direction with respect to system S is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

so the coordinates of the particle with respect to the S' system are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

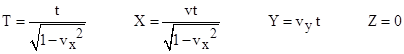

The first of these equations implies t = T(1 – vx2)1/2, so we can substitute for t in the expressions for X and Y to give |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The total squared speed V2 with respect to these coordinates is given by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

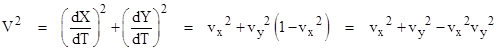

Subtracting 1 from both sides and factoring the right hand side, this relativistic composition rule for orthogonal speeds vx and vy can be written in the form |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

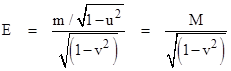

It follows that the total energy (neglecting stress and other forms of potential energy) of a ring of matter with a rest mass m spinning with an intrinsic circumferential speed u and translating with a speed v in the axial direction is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

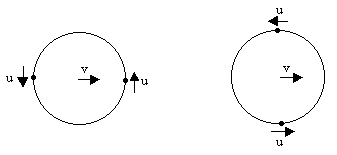

A similar argument applies to translatory motions of the ring in any direction, not just the axial direction. For example, consider motions in the plane of the ring, and focus on the contributions of two diametrically opposed particles (each of rest mass m/2) on the ring, as illustrated below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

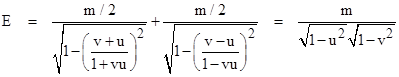

If the circumferential motion of the two particles happens to be perpendicular to the translatory motion of the ring, as shown in the left-hand figure, then the preceding formula for E is applicable, and represents the total energy of the two particles. If, on the other hand, the circumferential motion of the two particles is parallel to the motion of the ring's center, as shown in the right-hand figure, then the two particles have the speeds (v+u)/(1+vu) and (v–u)/(1–vu) respectively, so the combined total energy (i.e., the relativistic mass) of the two particles is given by the sum |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus each pair of diametrically opposed particles with equal and opposite intrinsic motions parallel to the extrinsic translatory motion contribute the same total amount of energy as if their intrinsic motions were both perpendicular to the extrinsic motion. Every bound system of particles can be decomposed into pairs of particles with equal and opposite intrinsic motions, and these motions are either parallel or perpendicular or some combination relative to the extrinsic motion of the system, so the preceding analysis shows that the relativistic mass of the bound system of particles is isotropic, and the system behaves just like an object whose rest mass equals the sum of the intrinsic relativistic masses of the constituent particles. (Note again that we are not considering internal stresses and other kinds of potential energy.) |

|

|

|

This nicely illustrates how, if the spinning ring was mounted inside a box, we would simply regard the angular kinetic energy of the ring as part of the rest mass M of the box with speed v, i.e., |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where the "rest mass" of the box is now explicitly dependent on its energy content. This naturally leads to the idea that each original particle might also be regarded as a "box" whose contents are in an excited energy state via some kinetic mode (possibly rotational), and so the "rest mass" m of the particle is actually just the relativistic mass of a lesser amount of "true" rest mass, leading to an infinite regress, and the idea that perhaps all matter is really some form of energy. |

|

|

|

But does it really make sense to imagine that all the mass (i.e., inertial resistance) is really just energy, and that there is no irreducible rest mass at all? If there is no original kernel of irreducible matter, then what ultimately possesses the energy? To picture how an aggregate of massless energy can have non-zero rest mass, first consider two identical massive particles connected by a massless spring, as illustrated below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Suppose these particles are oscillating in a simple harmonic motion about their common center of mass, alternately expanding and compressing the spring. The total energy of the system is conserved, but part of the energy oscillates between kinetic energy of the moving particles and potential (stress) energy of the spring. At the point in the cycle when the spring has no tension, the speed of the particles (relative to their common center of mass) is a maximum. At this point the particles have equal and opposite speeds +u and -u, and we've seen that the combined rest mass of this configuration (corresponding to the amount of energy required to accelerate it to a given speed v) is m/(1–u2)1/2. At other points in the cycle, the particles are at rest with respect to their common center of mass, but the total amount of energy in the system with respect to any given inertial frame is constant, so the effective rest mass of the configuration is constant over the entire cycle. Since the combined rest mass of the two particles themselves (at this point in the cycle) is just m, the additional rest mass to bring the total configuration up to m/(1–u2)1/2 must be contributed by the stress energy stored in the "massless" spring. This is one example of a massless entity acquiring rest mass by virtue of its stored energy. |

|

|

|

Another example – with far-reaching consequences – is the increase in an object’s rest mass when it absorbs massless electromagnetic radiation. Conversely, we can show that the rest mass of an object is reduced by E/c2 when it emits an amount E of electromagnetic energy, as explain at the end of Section 2.4. These were the scenarios that Einstein originally used to infer the inertia of energy. |

|

|

|

In retrospect, it’s clear that the energy-momentum vector of a particle is to be defined as [E, px, py, pz] where E is the total energy and px, py, pz are the components of the momentum, all with respect to some fixed system of inertial coordinates t,x,y,z. The rest mass m of the particle is then defined as the Minkowskian "norm" of the energy-momentum vector, i.e., |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If the particle has rest mass m, the components of its energy-momentum vector are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If the object is moving with speed u, then dt/dτ = γ = 1/(1–u2)1/2, so the energy component is equal to the transverse relativistic mass. The rest mass of a configuration of arbitrarily moving particles is simply the norm of the sum of their individual energy-momentum vectors. The energy-momentum vectors of two particles with individual rest masses m moving with speeds dx/dt = u and dx/dt = –u are [γm, γmu, 0, 0] and [γm, –γmu, 0, 0], so the sum is [2γm, 0, 0, 0], which has the norm 2γm. This is consistent with the previous result, i.e., the rest mass of two particles in equal and opposite motion about the center of the configuration is simply the sum of their relativistic masses, i.e., the sum of their energies. |

|

|

|

A photon has no rest mass, which implies that the Minkowskian norm of its energy-momentum vector is zero. However, it does not follow that the components of its energy-momentum vector are all zero, because the Minkowskian norm is not positive-definite. For a photon we have E2 – px2 – py2 – pz2 = 0 (where E = hν), so the energy-momentum vectors of two photons, one moving in the positive x direction and the other moving in the negative x direction, are of the form [E, E, 0, 0] and [E, –E, 0, 0] respectively. The Minkowski norms of each of these vectors individually are zero, but the sum of these two vectors is [2E, 0, 0, 0], which has a Minkowski norm of 2E. This shows that the rest mass of two identical photons moving in opposite directions is m = 2E = 2hν, even though the individual photons have no rest mass. |

|

|

|

If we could imagine a means of binding the two photons together, like the two particles attached to the massless spring, then we could conceive of a bound system with positive rest mass whose constituents have no rest mass. Indeed, as mentioned previously, the interaction between massless energy and the Higgs field is now known to be responsible for binding the energy so that it has rest mass. Also, in principle we could imagine photons bound together by the gravitational field of their energy. The ability of electrons and anti-electrons (positrons) to completely annihilate each other in a release of energy suggests that these actual massive particles are also, in some sense, bound states of pure energy, but what determines the characteristic masses of electrons and quarks is not not known. |

|

|

|

It's worth noting that the definition of "rest mass" is somewhat context-dependent when applied to complex accelerating configurations of entities, because the momentum of such entities depends on the space and time scales on which they are evaluated. For example, we may ask whether the rest mass of a spinning disk should include the kinetic energy associated with its spin. For another example, if the Earth is considered over just a small portion of its orbit around the Sun, we can say that it has linear momentum (with respect to the Sun's inertial rest frame), so the energy of its circumferential motion is excluded from the definition of its rest mass. However, if the Earth is considered as a bound particle during many complete orbits around the Sun, it has no net momentum with respect to the Sun's frame, and in this context the Earth's orbital kinetic energy is included in its "rest mass". |

|

|

|

Similarly the atoms comprising a "stationary" block of lead are not microscopically stationary, but in the aggregate, averaged over the characteristic time scale of the mean free oscillation time of the atoms, the block is stationary, and is treated as such. The temperature of the lead actually represents the kinetic energy of the constituent particles, but over a suitable length of time the particles are still stationary. We can continue to smaller scales, down to sub-atomic particles comprising individual atoms, and we find that the position and momentum of a particle cannot even be precisely stipulated simultaneously. In each case we must choose a context before we can apply the definition of rest mass. In general, physical entities possess multiple modes of excitation (kinetic energy), and some of these modes we may choose (or be forced) to absorb into the definition of the object's "rest mass", because they do not vanish with respect to any inertial reference frame, whereas other modes we may choose (and be able) to exclude from the "rest mass". In order to assess the momentum of complex physical entities in various states of excitation, we must first decide how finely to decompose the entities, and the time intervals over which to make the assessment. The "rest mass" of an entity invariably includes some of what would be called energy or "relativistic mass" if we were working on a lower level of detail. |

|

|