|

The Doctrine of Chance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chance, as we understand it, supposes the Existence of things, and their general known Properties: that a number of Dice, for instance, being thrown, each of them shall settle upon one or other of its Bases. After which, the Probability of an assigned Chance, that is of some particular disposition of the Dice, becomes as proper a subject of Investigation as any other quantity or Ratio can be. But Chance, in atheistical writings or discourse, is a sound utterly insignicant: It imports no determination to any mode of Existence; nor indeed to Existence itself, more than to non-existence; it can neither be defined nor understood: nor can any Proposition concerning it be either affirmed or denied, excepting this one, “That it is a mere word." |

|

Abraham de Moivre, 1735 |

|

|

|

Among those who fled France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes was the mathematician Abraham de Moivre, who emigrated to England and became friends with Isaac Newton. (It’s interesting to compare the emigration of so many talented Protestants to England due to the religious persecution in France in the late 1600s with the mass emigration of Jewish scientists from Germany to England and the United States during the 1930’s.) Newton seems to have held De Moivre in high regard; when questioned about mathematics in his later years he would sometimes say “Go to Mr. De Moivre, he knows these things better than I do”. De Moivre is perhaps best remembered today for being among the first to note the relation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

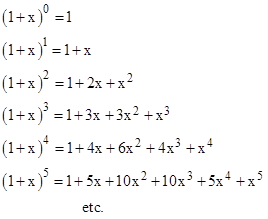

but he also did early work in the theory of probability and applied statistics (which he applied to gambling problems as well as actuarial tables). Much of this was presented in his book “Doctrine of Chances” (1718). In a later paper, entitled “Approximatio ad summam terminorum biomii (a + b)n in seriem expansi” (1733) he made an interesting observation concerning the coefficients of the binomial expansions. (Ironically, the binomial expansions were the source of one of Newton’s most important discoveries in mathematics over 60 years earlier.) The first several of these expansions are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Letting C(m,n) denote the coefficient of xn in the expansion of (1 + x)m, it’s easy to show that the coefficients satisfy the recurrence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and we also have (from Newton’s binomial theorem) the closed-form expression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

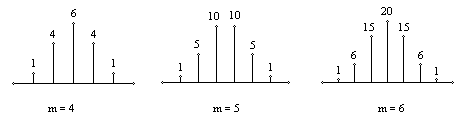

The sum of the coefficients of (1 + x)n is obviously 2n so, if we divide the coefficients by 2n, the sum of the normalized coefficients of each polynomial will equal 1. Also, the coefficients are clearly symmetrical, and we can align the central values by shifting the n index by m/2. De Moivre noticed a remarkable fact about these normalized coefficients, namely, that if we scale the normalized coefficients by the square root of m, and scale the indices by the reciprocal of this square root, all the coefficients appear to lie on (or very close to) a single curve. The figure below shows the re-scaled coefficients for m = 4, 5, and 6. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

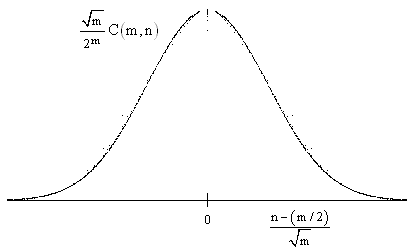

Continuing on in this way, a plot of the normalized and re-scaled coefficients for the first 60 binomial expansions is shown below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

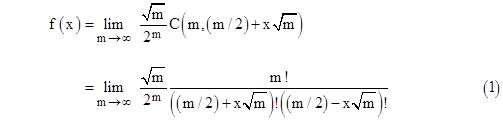

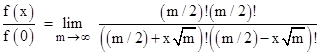

De Moivre saw that, as m increases, the coefficients converge on this single curve. He also found the form of the equation of this ultimate curve. His reasoning might have been something like this: Letting x denote the horizontal coordinate, we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and therefore |

|

|

|

|

|

Substituting this into the expression for the scaled normalized binomial coefficients, the ultimate function can be expressed as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now consider the ratio |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Since we need to evaluate the right hand side in the limit as m goes to infinity, we can just as well set m = 4k2 and evaluate in the limit as k goes to infinity. Thus we can write |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

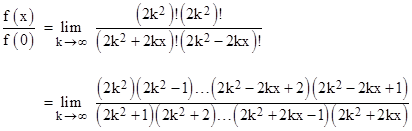

Noting that each factor in the numerator and the respective factor in the denominator sum to 4k2 + 1, and that the factors increase by 1 in the numerator and decrease by 1 in the denominator, we can write the above as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

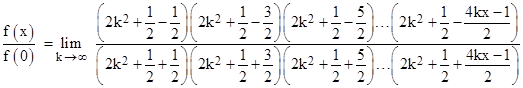

Dividing through the matching factors in the numerator and denominator by 2k2 + 1/2 and noting that the 1/2 will become negligible in the limit, we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

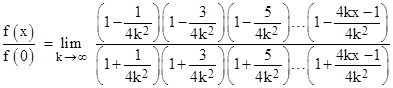

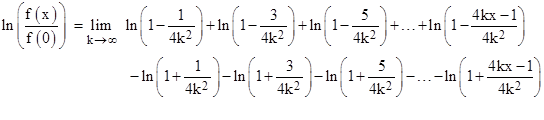

Taking the natural log of both sides, and using the fundamental additive property of the logarithm, this can be written as |

|

|

|

|

|

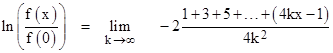

Now, making use of the well-known expansion ln(1 + x) = x – x2/2 + …, and noting that all but the first terms in these expansions will vanish in the limit as k increases to infinity, we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

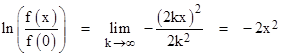

The sum of the first N odd numbers is the square of (N+1)/2, so the above reduces to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Taking the exponential of both sides, we find that |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

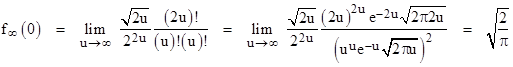

where f∞(0) denotes the limiting value of f(0). To determine this value we can make use of Stirling’s formula |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

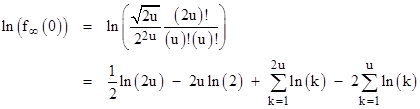

Taking equation (1) with x = 0 and m = 2u, and substituting for the factorials from Stirling’s formula, we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

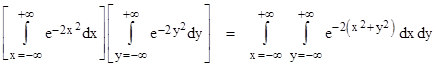

A different approach to determining f∞(0) is to note that we require the integral of f(x) over the range x = –∞ to +∞ to equal 1. Therefore, we need only evaluate the integral of f(x)/f(0), and then choose f(0) to make the integral of f(x) equal to 1. The usual method is to consider two such distributions multiplied together as follows. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

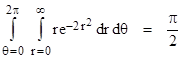

Transforming to polar coordinates by the substitution x = r cos(θ) and y = r sin(θ) and noting that the incremental area on this two-dimensional surface is dA = dydx = rdθdr, we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The desired integral is the square root of this quantity, so we (again) have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and therefore De Moivre’s ultimate curve can be written in the form |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

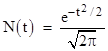

If we re-scale the x axis in terms of the new variable t = 2x we must double the scaling of f to keep the same integral, so we define the function N(t) = f(t/2)/2, which gives the usual form of the standard normal distribution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oddly enough, De Moivre says he originally just assessed the constant factor numerically, and he says it is the number whose logarithm is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

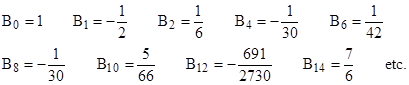

He wrote this in 1733, but he says he had the results some 12 years earlier, so he evidently knew the above series for ln(2π)/2 in 1721. De Moivre mentioned this series several times in his Doctrine of Chance, but never explained its origin, nor even defined the general term. He says only that he found its convergence to be slow. This is all rather odd, for several reasons. First, the series isn’t convergent at all, it is actually divergent. Second, it is evidently something like an Euler-Maclarin expansion, since the terms seem to be |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where Bk represents the Bernoulli numbers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is somewhat remarkable, considering that Jacob Bernoulli didn’t write his essay introducing what de Moivre called the Bernoulli numbers until about 1717, and the Euler-Maclaurin series wasn’t published by Euler until 1731. It’s particularly odd since de Moivre says he didn’t know Stirling’s formula for the factorial function at the time when he originally found his results on the binomial coefficients and their asymptotic curve. Recall that the coefficient of his ultimate curve was the limiting value of f(0), which we will denote by f∞(0), and since he didn’t know Stirling’s formula at that time (nor did he know how to integrate the normal density), he attempted to evaluate the logarithm of f∞(0) as follows |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

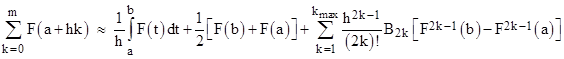

in the limit as u goes to infinity. Now, the Euler-Maclaurin formula allows us to write (asymptotic) series for summations in terms of the Bernoulli numbers, and this is evidently how de Moivre proceeded – although it’s surprising that he knew this method as early as 1721. In any case, the general Euler-Maclaurin formula can be written as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

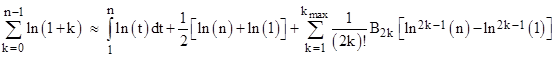

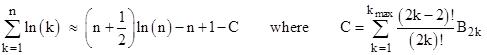

where mh = b – a and superscripts on F denote derivatives. The symbol kmax represents the number of terms in the summation, which must be chosen judiciously, because the series is divergent. Taking F to be the natural log function, and setting a = h = 1 and b = n, this would have given de Moivre the expression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

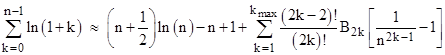

Evaluating the integral in the first term on the right hand side, and noting that the derivative of the natural log are |

|

|

|

|

|

we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

At this point de Moivre could have reasoned that, in the limit as n goes to infinity, the first term in the square brackets becomes insignificant compared with -1, so he could re-write this equation (shifting the summation limits and argument by 1 on the left hand side) as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

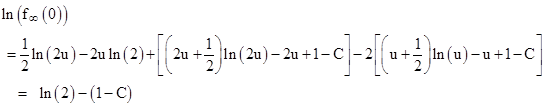

Making use of this to simplify the summations in the previous expression for f∞(0), we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

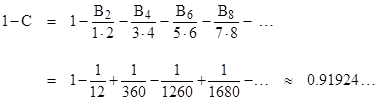

Therefore, according to this reconstruction of de Moire’s reasoning, we have f∞(0) = 2e–(1–C). This leads him to evaluate the series mentioned previously, i..e., |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

De Moivre seems to have been slightly annoyed with himself for failing to notice the closed form expression for this number, leaving it to James Stirling to complete the derivation. Referring to the quantity e(1–C) as “B”, de Moivre wrote |

|

|

|

When I first began that inquiry, I contented myself to determine at large the value of B, which was done by the addition of some terms of the above-written series; but as I perceived that it converged but slowly, and seeing at the same time that what I had done answered my purpose tolerably well, I desisted from proceeding farther till my worthy and learned friend Mr. James Stirling, who had applied himself after me to that inquiry, found that the Quantity B did denote the Square-root of the Circumference of a Circle whose Radius is Unity (i.e., the square root of 2π)… But altho' it be not necessary to know what relation the number B may have to the Circumference of the Circle, provided its value be attained, either by pursuing the Logarithmic Series before mentioned, or any other way; yet I own with pleasure that this discovery, besides that it has saved trouble, has spread a singular Elegancy on the Solution. |

|

|

|

However, de Moivre wasn’t really as close as he apparently thought he was to having determined the value of the scale factor, because he says “I perceived that [the series] converged but slowly”, whereas in fact (as mentioned above) the series actually diverges. Hence it could never lead to an exact determination of the scale factor. |

|

|

|

The later editions of De Moivre’s book contain an interesting aside that sheds light on the uneasy attitude of 18th century scholars toward issues of credit and priority for their intellectual efforts. On one hand they wished to appear uncaring as to whether or not they received credit for things, as if such caring would be unseemly vanity, and they were content to leave the judgements of history and their fellow men to chance. But on the other hand, when push came to shove, they intensely craved credit and renown. (De Moivre’s friend Isaac Newton was a prime example of this, since Newton originally affected not to care about credit for his works, but eventually became embroiled in a bitter dispute with Leibniz over who deserved credit for invention of calculus.) Here’s an excerpt from de Moivre’s book discussing how he had originally found the solution to a certain problem in 1708, but hadn’t published it, and then in 1713 two solutions appeared, one by Mr. de Monmort and one by Nicholas Bernoulli. De Moivre wrote |

|

|

|

As those two Solutions seemed to me, at first sight, to have some affinity with what I had found before, I considered them with very great attention; but the Solution of Mr. Nicolas Bernoulli being very much crouded with Symbols, and the verbal Explication of them too scanty, I own I did not understand it thoroughly, which obliged me to consider Mr. de Monmort's Solution with very great attention: I found indeed that he was very plain, but to my great surprize I found him very erroneous; still in my Doctrine of Chances I printed that Solution, but rectified and ascribed it to Mr. de Monmort, without the least intimation of any alterations made by me; but as I had no thanks for so doing, I resume my right, and now print it as my own. |

|

|