|

The Moszkowski Affair |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

At a meeting of the Berlin Scientific Association in October of 1910, Henri Poincare spoke on the subject of the “New Mechanics”. Among the small number of people who came to listen was a Polish author named Alexander Moszkowski, who noted that Poincare was filled with caution and misgivings about the new ideas he was describing, ideas which Poincare evidently attributed to someone named Albert Einstein, a name that Moszkowski had never heard before. Moszkowski found the ideas “staggering”. |

|

|

|

Oblivious of the doubts of the lecturer, I was swept along under the impetus of this new and mighty current of thought. This awakened two wishes in me: to become acquainted with Einstein's researches as far as lay within my power, and, if possible, to see him once in person. |

|

|

|

This is remarkable, because it is usually said that Poincare never referred (publicly) to Einstein’s work on relativity theory, and yet Moszkowski came away from Poincare’s talk with the clear and vivid impression that there was a “new and mighty current of thought” in physics due primarily to Albert Einstein. Just two years earlier, in 1908, Poincare had published the book Science and Method, and Part III of that book was entitled “The New Mechanics”, so we can take that as an indication of the subject matter of his talk in Berlin. Lorentz’s theory and the principle of relativity were he main focus. Of course, Einstein’s name was not mentioned in Science and Method, but he must have been featured very prominently in Poincare’s talk, at least if we can judge from the reaction of Moszkowski. On the other hand, it seems that Poincare wasn’t exactly singing Einstein’s praises, since Moszkowski recalls that Poincare seemed to be |

|

|

|

…still clinging to the hope that the new doctrine he was expounding would yet admit of an avenue leading back to the older views. This revolution, so he said, seemed to threaten things in science which a short while ago were looked upon as absolutely certain, namely, fundamental theorems of classical mechanics, for which we are indebted to the genius of Newton. For the present this revolution is of course only a threatening spectre, for it is quite possible that, sooner or later, the old established dynamical principles of Newton will emerge victoriously. |

|

|

|

If nothing else, this again confirms that Poincare was indeed talking about relativity, and he clearly gave at least one of his listeners the impression that it was largely the work of Einstein. Moszkowski claims that, during this talk, Poincare had “confessed that it caused him the greatest effort to find his way into Einstein's new mechanics”. Moszkowski later noted with satisfaction that Poincare recommended Einstein for a professorship, which he (Moszkowski) interpreted as a sign that Poincare’s doubts about Einstein’s work on the theory of relativity had been overcome. This refers to one of the most famous letters of recommendation in the history of physics: |

|

|

|

Herr Einstein is one of the most original minds that I have ever met. In spite of his youth he already occupies a very honourable position among the foremost savants of his time. What we marvel at in him, above all, is the ease with which he adjusts himself to new conceptions and draws all possible deductions from them. He does not cling tightly to classical principles, but sees all conceivable possibilities when he is confronted with a physical problem. In his mind this becomes transformed into an anticipation of new phenomena that may some day be verified in actual experience... The future will give more and more proofs of the merits of Herr Einstein, and the University that succeeds in attaching him to itself may be certain that it will derive honour from its connexion with the young master. |

|

|

|

Moszkowski reproduced this letter in his book, but doesn’t say how he acquired it. One would think that letters of this kind are usually kept confidential, but apparently it was in the public domain at least by 1920. It is certainly a glowing recommendation, although I’ve always wondered if there was just a tinge of irony in Poincare’s statement that Einstein was “one of the most original minds” he had ever met, considering the extent to which Poincare himself had anticipated so many of Einstein’s ideas. Still, it seems that Einstein’s interpretation of special relativity was genuinely difficult for Poincare to grasp. After meeting both Lorentz and Poincare at the Solvay conference in 1911, Einstein wrote (in a letter to his friend Heinrich Zangger) that |

|

|

|

H. A. Lorentz is a marvel of intelligence and tact. He is a living work of art! In my opinion he was the most intelligent among the theoreticians present. Poinkare [sic] was simply negative in general, and, all his acumen notwithstanding, he showed little grasp of the situation. |

|

|

|

Oddly enough, this letter is the only time I’ve ever seen Poincare’s name rendered as “Poinkare”, and it appears twice in this letter, both times with the “k”. It is even more strange considering that Einstein had been an avid reader of Poincare’s works for many years, and had just come from a conference, the literature for which lists Poincare’s name consistently with a “c”. Not to mention the fact that Einstein himself had referred to Poincare in his own published works, always with the correct spelling. As far as I know, he never previously or subsequently spelled Poincare’s name with a “k”, except for the two occurrences in this letter to Zangger. Curious. Another oddity is that Pais quoted the very same letter to Zangger, giving not only an English translation but also the (presumably) original German, which according to Pais is as follows |

|

|

|

Poincare war (gegen die Relativitatstheorie) einfach allgemein ablehnend , zeigte bei allem Scharfsinn wenig Verstandnis fur die Situation. |

|

|

|

The parenthetical “(in regard to relativity theory)” is quite prominent here, but no such phrase appears in the translation of the letter given in Einstein’s Collected Paper. It’s a fairly significant phrase, so it’s hard to imagine Pais inserting it on his own, but equally hard to imagine the translators of the Collected Papers leaving it out. Also, notice that Poincare is spelled with a “c” in Pais’s version. What was Pais’s source for the original German text of this letter? Could he perhaps have been taking notes somewhere, and just automatically corrected the spelling, and jotted down the parenthetical statement as a note to himself, and then later thought it was part of the original quote? |

|

|

|

In 1914, just prior to the outbreak of the first world war, Einstein moved from Zurich to Berlin, where he completed his work on the general theory of relativity by December of 1915. This was still four years before the announcement of the results of the eclipse expedition in 1919, so Einstein was not yet the world-wide celebrity he was to become, but he was already a noted figure in Berlin. Early in 1916, as the battle of Verdun was raging on the Western Front, and just weeks after Einstein completed the general theory, Moszkowski was finally able to arrange a meeting with the source of “the new and mighty current of thought”. |

|

|

|

I wrote [Einstein] a letter asking him to honour with his presence one of the informal evenings instituted by our Literary Society at the Hotel Bristol. He was my neighbour at the table, and chatted with me for some hours. Nowadays his appearance is known to everyone through the innumerable photos which have appeared in the papers, [but] at that time I had never seen his countenance before, and I became absorbed in studying his features, which struck me as being those of a kindly, artistically inclined, being... He seemed vivacious and un-restrained in conversation... It was certainly most delightful. Yet at moments I was reminded of a male sphinx, suggested by his highly expressive enigmatic forehead. |

|

|

|

At this time of this meeting, Moszkowski was 65 years old and Einstein was 37. (Given Einstein’s interest in music, he surely must have known of Moskowski’s younger brother Moritz, who had been a famous and very popular composer and pianist in the late 19th century when Einstein was growing up.) As a writer, it seems that from the start Moszkowski had in mind the ambition to be Einstein’s “Boswell”, and took every opportunity to meet with him and engage him in discussions on all kinds of topics. Eventually Moszkowski and his wife Bertha became close friends with Einstein and his cousin and (after they were married in 1919) wife Elsa. |

|

|

|

Following the sensational announcement of the results of the eclipse expedition in November of 1919 it seemed as if Einstein and his theory of relativity became the chief topic of discussion in every household. The public appetite for anything having to do with Einstein was insatiable, so it obviously presented a marvelous opportunity for Moszkowski to write his book. With Einstein’s cooperation, Moszkowski conducted a series of interviews, and prepared to publish a book that was to be entitled “Conversations with Einstein”. However, as luck would have it, in 1920, Einstein came under severe attack by a group of individuals, notably Lenard, Stark, and Gehrcke, who charged (among other things) that Einstein was a vain publicity seeker. Just as Moszkowski’s book was about to be printed (in 1921), several of Einstein’s friends got wind of it, and urged Einstein to withdraw his consent. These friends, especially Max and Hedi Born, argued that the book would play into the hands of Lenard and the other members of the Anti-Relativity Company. |

|

|

|

The letters written by the Borns are remarkable in tone. In later years Max admitted that they probably went overboard, but at the time it was considered scandalous for a scientist to behave like (and be treated like) a celebrity. The first to write was Hedi: |

|

|

|

Today a very serious, friendly word to you. You must withdraw the permission given to Moszkowski to publish the book “Conversations with Einstein”, and to be precise, immediately and by registered mail. Nor should it be allowed to appear abroad either… That man doesn’t have the slightest inkling about the essence of your character… if he understood, or even had a glimmer of respect and love for you, he would neither have written this book nor wrung this permission out of your good nature. [If you allow this book to be published], you will be quoted everywhere, your own jokes will be smirkingly flung back at you… couplets will be written, an entirely new, awful smear campaign will be let loose, not just in Germany, no, everywhere, and your revulsion of it will choke you… |

|

|

|

Hedi had begun by saying that she wished she had “the persuasiveness of an angel” in order to convince Einstein not to allow publication, and her letter continued with a very heavy dose of angelic persuasion |

|

|

|

It will be no use any more to protest that you gave permission out of weakness, out of good nature. No one will believe it. The fact will remain that a man in his early forties gave permission to one of the most despicable German writers to record his conversations. If I did not know you, I would not concede to a single other living soul, to whom the above fact applied, innocence. I would definitely believe it was vanity. For everyone, except for about 4-5 of your friends, this book would constitute your moral death sentence. |

|

|

|

After noting that the book would confirm the accusations that he was a publicity-seeker, and that it would be the end of Einstein’s tranquility “everywhere and for good”, she offered her appraisal of Moszkowski’s motives: |

|

|

|

Now I see very clearly why Moszk always imposed himself upon you. He caught wind of the goldmine. For every one mark spent on each egg that he thrust upon you during your illness, what a well-invested speculation: for each mark he now earns a thousand. |

|

|

|

Speaking of the goldmine, it was probably not lost on Einstein that, just five days earlier, Hedi Born had written to ask a favor: |

|

|

|

My husband feels like slaughtering the American golden calf and, by lecturing there, earn the means to build himself a little house in Gottingen, according to his wishes. So, if you still have occasion to recommend someone for lectures there, please do name Max. |

|

|

|

In fact, the irony apparently wasn’t missed by the Borns either, because just a couple of days after Hedi’s stern letter of friendly advice about the book, Max wrote to re-affirm that Einstein “must shake off Moszkowski” (otherwise “Lenard and Gehrcke will be triumphant”), just as Hedi has counseled, but then he added |

|

|

|

She does already regret though, having otherwise also wanted to turn your name into gold by sending me to America. |

|

|

|

Incidentally, Hedi’s mention of Einstein’s “illness” was a reference to his breakdown in 1918, when he collapsed and was bed-ridden for several months. During this time he was visited often by Moszkowski (as well as by Hedi herself), and some accounts of the conversations that took place during these visits were included in the book. On one such visit, Moszkowski thought he should not stay long, but Einstein insisted that he stay awhile, to converse (as Moszkowski said) “about amusing little problems as usual”. |

|

|

|

Einstein: So, let’s make a start. You have probably some conundrum weighing on your mind. |

|

|

|

Moszkowski: I have been troubled by something in connexion with Kepler's second law. It almost robbed me of my night's sleep. My thoughts kept returning to a certain question, and I should like to know whether there is any sense in the question itself at all. |

|

|

|

Einstein: Let us hear it! |

|

|

|

Moszkowski: The law in question states that every planet in describing its elliptic path, sweeps out with its radius vector equal sectorial areas in equal intervals of time. But this seems only half a law, for the radius vectors are only considered drawn from the one focus of the ellipse, namely, the gravitational centre. Now, another focus exists, that may be situated in space somewhere, perhaps far away in totally empty regions, if we assume the orbit to be very eccentric. My question is: What form does this law take if the radius vectors are drawn from this second focus and if the corresponding sectorial areas are considered, instead of these quantities being referred to the first focus exclusively ? |

|

|

|

Einstein: This question is not devoid of sense, but it serves no useful purpose. It may be solved analytically, but would probably lead to very complicated expressions, that would be of no interest for celestial mechanics. For the second focus is only a constructive addition, that has nothing real in space corresponding to it. What else is troubling you ? |

|

|

|

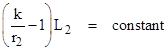

I wonder if Moszkowski actually dreamed up this problem himself, or if it was from some compendium of mathematical puzzlers. He was, after all, the author of a book entitled “1000 of the Best Jewish Jokes”, so he was no stranger to compilations of trivia. In any case, Einstein’s response seems a bit disappointing. It could, perhaps, be seen as an example of his ability to quickly discern physically meaningless questions, but he was also known to be fond of simple problems in plane geometry, so it’s surprising that he didn’t rise to the bait. Actually he was too pessimistic in thinking that it “would probably lead to very complicated expressions”. The law of equal areas merely expresses the conservation of angular momentum per unit mass L = ωr2 where w is the angular speed and r is the distance from the central body. Now, by the well-known fact that rays from one focus of an ellipse are reflected to the other focus, it follows that the two radial rays make equal angles with the tangent to the ellipse, and hence ω1r1 = ω2r2 where subscripts denote the angular speeds and distances with respect to the two foci. Multiplying through by r1, we get L1 = (r1/r2)L2. Of course, we also know r1 + r2 = k for some constant k (the defining property of an ellipse), so the conserved quantity about the empty foci is not L2 but rather |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

But Einstein obviously wasn’t interested in thinking about this question, so Moszkowski moved on. |

|

|

|

Moszkowski: My next difficulty is a little problem that sounds quite simple and yet is sufficiently awkward to make one rack one's brains. It was suggested to me by an engineer who certainly has a keen mind for such things, and yet, as far as I could judge, he did not get a solution for it. It concerns the position of the hands of a clock." |

|

|

|

Einstein: You surely are not referring to the children's puzzle of how often and when both hands coincide in position? |

|

|

|

Moszkowski: By no means. As I said just now, it is really quite perplexing. Let us assume the position of the hands at twelve o'clock, when both hands coincide. If they are now interchanged, we still have a possible position of the hands, giving an actual time. But, in another case, say, exactly six o'clock, we get a false position of the hands, if we interchange them, for on a normal clock it is impossible for the large hand to be on the six whilst the small hand is on the twelve. The question is now : When and how often are the two hands situated so that when they are interchanged, the new position gives a possible time on the clock? |

|

|

|

Einstein: There, you see, that is just the right kind of distraction for an invalid. It is quite interesting, and not too easy. But I am afraid the pleasure will not be of great duration, for I already see a way to solve it. |

|

|

|

This too seems suspiciously like a canned puzzle, but at least it succeeded in capturing Einstein’s interest. Moszkowski then described how Einstein, supporting himself on his elbow, sketched a diagram representing the conditions of the problem, and then proceeded to work out the answer. |

|

|

|

I can no longer recollect how [Einstein] arrived at the terms of his equation, [but] the result soon came to hand in a time not much longer than I had taken to enunciate the problem to him. It was a so-called indeterminate (Diophantic) equation between two unknowns, that was to be satisfied by simple integers only. He showed that the desired position of the hands was possible 143 times in 12 hours, an equal interval separating each successive position. |

|

|

|

It would be interesting to know what picture Einstein drew to represent the conditions of this problem, but presumably it simply conveyed the two conditions relating two times t1 and t2 with swapped positions of the hour and minute hands |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where ω = 2π/12 rad/hour, and m and n are arbitrary integers, from which we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The numerator of t2 (for example) can be set to any integer from 0 to 142, giving the 143 uniformly distributed values of t1 around the dial for which the conditions of the problem are satisfied. Hence beginning at 12:00 another solution occurs every 5 minutes and 2.097902… seconds. Without loss of generality we can take m = 0, so we have t1 = (144/143)n hours and t2 = (12/143)n hours, with the understanding that we evaluate modulo 12 hours. Incidentally, the difference between these swapped times is t2 – t1 = (12/13)n, so there are only 13 distinct differences, in complementary pairs. |

|

|

|

On the subject of puzzles, one other example from Moszkowski’s book is interesting, not so much for the puzzle itself, or even the solution, but for the light it sheds on how biographers do their work. Here is how Moszkowski tells the story |

|

|

|

On another occasion a space-problem dealing with dress came up for discussion: Can a properly dressed man divest himself of his waistcoat without first taking off his coat? Einstein at once attacked it with enthusiasm, as if it were an exercise in mechanics, the body being the object; he solved it in a trice, practically, with a little energetic manipulation, much to the amazement and joy of the beholder… |

|

|

|

So, this was another of Moszkowski’s puzzles, which Einstein duly solved. Compare this with the following anecdote from Clark’s well-regarded 1971 biography |

|

|

|

When a group of eminent friends called for him one evening, [Einstein] accepted a bet to take off his waistcoat without first removing his coat. He was wearing his only dress suit, but immediately began a series of elaborate contortions. These continued for some while. It seemed he would have to pay up. Then, with a final tortuous twist he did the trick, triumphantly waving his crumpled waistcoat and exploding into his long deep belly laugh. |

|

|

|

Despite the fact that Moszkowski was (according to Frau Born) “one of the most despicable German writers”, and Clark was an renowned and well-respected biographer, I would venture to guess that Moszkowski’s first-hand account is fairly accurate and Clark’s is almost completely fabricated. A group of eminent friends? A wager? A Houdini act with an actual waist coat, as opposed to solving a puzzle? Waving the crumpled waistcoat in triumph and “exploding into a long deep belly laugh”? All this was just Clark’s imagination, embellishing on one of Moszkowski’s anecdotes, and without reference to the “despicable” source of the (rather slight) factual content of the anecdote. |

|

|

|

Returning to the saga of Moszkowski’s scandalous book, Einstein wrote to Max Born |

|

|

|

Your wife wrote me an incensed letter about the book by Mr. M. Objectively she is right, although not in her severe judgment of M. I have informed the latter in a registered letter that his magnificent opus is not allowed to be printed. |

|

|

|

He added the postscript “With hearty thanks to your wife”. Born’s letter, written before receipt of the above, was remarkably forceful and patronizing. He added that if Moszkowski indicated his intent to publish over Einstein’s objections, Einstein was to obtain an legal injunction, prohibiting publication of the book, and this action should be communicated to the newspapers. |

|

|

|

I beseech you, do as I write. Otherwise, Farewell Einstein! Then your Jewish “friends” [i.e., Moszkowski] will have achieved what the anti-Semitic gang were unable to do. Forgive the insistence of my letter, but it concerns all that is dear to me (and Planck, Laue, et al). You don’t understand. In such things you are a little child. You are loved and you must obey; that is, perspicacious people (not your wife). If you don’t want anything more to do with this business, then give me full authority in writing. I shall drive to Berlin if necessary, or to the North Pole. |

|

|

|

Along with this letter Born enclosed an advertisement (that had reached him “from various quarters”) from the bookseller’s periodical Buchhandler Borsenblatt, which seems to have been particularly tasteless, and about which he simply said “Commentary superfluous”. Einstein seems to have taken the advice to heart. Shortly thereafter, while vacationing in Sigmarigen with his two young sons, he wrote to Elsa, asking her to “console Moszkowski. His book about me must not appear. It would be catastrophic.” When he got back to Berlin, a letter from Bertha Moszkowski was waiting for him. She wrote |

|

|

|

On that terrible Friday when your letter arrived, Alex immediately dropped everything to fulfill your wish. At 10 o’clock the publisher was over here with us and, as he saw the state my husband was in, and heard his earnest pleas, he initially granted him his request, and telegraphed right away to Leipzig to stop the printing of the book, which is almost finished…On Monday however both publishers declared that it was impossible for them to keep their word… they could not expose themselves to this disgrace before the many booksellers who have already placed their orders… All my husbands suggestions were to no avail, he was ready to sacrifice anything… but the publishers absolutely do not want to give up the large profits they are anticipating. |

|

|

|

She went on to explain that the forward to the book would state that Einstein had not read it, and that Moszkowski was solely responsible for the authorship. In addition, the title of the book was changed to “Einstein the Searcher”. Bertha then couldn’t resist commenting on the motives of those who had advised Einstein to suppress the book. |

|

|

|

How few of your friends and counselors are completely free from envy. Don’t they all want something from you? Don’t they all use your name to their advantage? …Born’s biography of you is certainly enthusiastic, and could never hurt you… |

|

|

|

The latter statement was presumably a reference to the biographical sketch that Born had included, along with a photograph of Einstein, at the beginning of his 1920 book “Einstein’s Theory of Relativity”. Even this was regarded as unseemly by the standards of the day. Max von Laue, one of Einstein’s best friends, had written to Born that he “and many colleagues would take umbrage at the photograph and the biography”. Hence Born did not exactly hold the moral high ground when it came to publicizing Einstein. In fact, it could be argued that it was the personalization of relativity in the writings of scientists like Born, rather than the writings in the popular press by people like Moszkowski, that constituted the basis of the charges of Einstein’s critics. |

|

|

|

Bertha added what seems to have been a heart-felt plea for sympathy: |

|

|

|

How happy my husband was at first that the book was to appear. Now he has been deprived of his joy by this unfortunate incident… we will be happy again only when we know for certain that your friend Born’s persuasiveness does not withstand the facts. |

|

|

|

Evidently there was no mystery as to who was advising Einstein on this matter. One suspects that the Borns and the Moszkowski’s were not the best of friends. A few days later, Einstein wrote (from Holland) again to Max Born: |

|

|

|

I categorically forbade appearance of the book by M. Ehrenfest and Lorentz advise against court action, which would only heighten the scandal. The whole business is a matter of indifference to me, along with the clamor and opinion of all persons. So nothing can happen to me. In any case, I applied the strongest means available outside the courts, threatening in particular with a break in relations. By the way, M. really is preferable to me than Lenard and Wein. For the latter cause problems for the love of making a stink, and the former only in order to earn money (which really is more reasonable and better). I shall live through all that awaits me like an uninvolved spectator and not let myself be agitated any more as at Bad Nauheim [where Einstein had publicly debated Lenard about relativity]. It is completely incomprehensible to me that I could have so utterly lost my sense of humor in such bad company… |

|

|

|

He concluded the letter by noting that Lorentz had recently lectured about Born’s lattice equilibriums, and Einstein commented that Lorentz is “such an admirable person!” (By the way, Einstein’s acceptance of Moszkowski’s profit motive is reminiscent of Newton’s answer to why he had chosen Bentley to publish the second edition of Principia. Newton answered that Bentley "was covetous & loved money & therefore I lett him that he might get money".) Born responded, saying he was glad Einstein had acted forcefully against the book, adding that although Einstein could slip away to Holland, “we are stuck here in the land of Weyland, Lenard, Wein, and their cohorts”. (Weyland was not a scientist, but rather a sort of con man who had been largely responsible for organizing the Anti-Relativity Company.) Following this, Born offered some fascinating comments about his views on several of their mutual acquaintances. |

|

|

|

I am glad that all is going so well for you in Holland. But you must not be annoyed with me if, after the last incidents, I doubt your knowledge of human nature so strongly as not to share your admiration for Lorentz. You see Lenard and Wine as devils and Lorentz as an angel. Neither is quite accurate. The former suffer from a political sickness that is widespread in our famished country and is not at all based on innate malice. While I was in Gottingen just now, I saw Range emaciated to a skeleton and correspondingly embittered and changed. Only then did it become clear to me what is happening around here. By contrast, Lorentz: he refused to write something for Planck's 60th birthday, you know. I hold that very much against him. You are welcome to tell him so. One can, of course, have a different opinion from Planck, but his honest, noble character can only be doubted by those lacking in such qualities. Lorentz evidently fears a loss of his contented Entente friends more than he values justice. The fact that he lectures about my lattice calculations in his course does not charm me. Besides, that is not the only thing I have against him, but I am not writing just to complain; rather, I frankly confess that when I know you are with Lorentz, Ehrenfest, Weiss, and Lange in, I find that much more welcome than socializing with the author of Freibad der Musen. |

|

|

|

Freibad der Musen (Swimming Pool of the Muses) was one of Moszkowski’s previous books, about which Hedi Born had written to Einstein |

|

|

|

…the level of this book disgusts me so much that I wrote the enclosed nasty remarks which – this I swear to you – I will publish if you do not immediately withdraw your permission [for the publication of Conversations with Einstein]. |

|

|

|

It may be worth mentioning that Hedwig Born was herself a playwright, so she definitely had a flair for the dramatic. Einstein once commented to Max Born that “your wife’s letters are masterpieces”. Could her view of Moszkowski have been tainted by professional resentment of a fellow writer, one who she regarded as totally without literary merit, despite the commercial success of his publications? And is it possible that Hedi thought Moszkowski had poached on her subject? Surely a writer such as Hedi must have been tempted to write about Einstein herself at some point. |

|

|

|

As noted above, Max Born had sent Einstein a particularly tasteless advertisement promoting Moszkowski’s upcoming book. Einstein sent it along to Moszkowski as part of the justification for why he was withdrawing his permission to publish the book. He must have written rather forcefully, because it prompted Bertha to send another letter in reply: |

|

|

|

The heavy, unfair blow that you delivered in the letter my husband received today lands on a completely innocent person. At all events, the Buchhhandler Borsenblatt that was sent to you is not meant for the general public, and came into your hands only through the indiscretion or malice of some publisher. Not even newspapers take these advertisements, and you must believe me that neither my husband nor I have ever seen that paper nor know about the advertisement… In the meantime, you have probably learned that the title [of the book] has been changed, hence that your personal collaboration is completely eliminated; you likewise now know that much more that could in any way have exposed you to attack has been removed from the book. |

|

|

|

Hence the book ultimately published in 1921 under the title “Einstein the Searcher” was denuded of much personal material. This must explain, at least partly, the fragmentary and disjointed quality of the book. (In 1970 the original book was finally published under its original title – Conversations with Einstein – although I don’t know the circumstances of its publication.) Bertha concluded her letter by saying |

|

|

|

More loyal friends than we are to you, you cannot have, and your hard words could not have hit anyone as heavily as they hit us. The dreadful advertisement appeared once in the Buchhandler Blatt; after my husband learned of it he, like your wife, extracted from the publisher the promise that nothing appear, even there, that he had not seen and authorized. My husband is incapable of writing at the moment; that is why I have taken it on. We have only one wish, that you gain the firm belief that my husband neglected nothing in complying with your wish, but failed before the impossible, and that when you know all the accompanying facts you will take back your hard words. |

|

|

|

When Max Born published his correspondence with Einstein half a century later, he seems to have been slightly embarrassed by how strenuously he had urged Einstein to eschew publicity. He admitted that |

|

|

|

[Today] the publicity we fought against is commonplace, and spares no one. Every one of us is interviewed and paraded before the general public in the papers, on the radio, and television… no one thinks anything of it. |

|

|

|

Oddly enough, in his account of the episode, and in the reproduced correspondence in Born’s book, the name Moszkowski is everywhere replaced with “X”. It’s hard to imagine that this would be sufficient to conceal the man’s identity, but perhaps it was Born’s way of exonerating Moszkowski, which may have seemed necessary, considering that Born’s publication of his “correspondence with Einstein” was so similar in spirit to Moszkowski’s “conversations with Einstein”. Born concluded one of his many published essays on Einstein and relativity by saying |

|

|

|

I conclude my address by apologizing that it was so long. By my friendship with Einstein was one of the greatest experiences of my life, and ‘Ex abundantia enim cordis os loquitur’, or in good Scots ‘Neirest the heart, neirest the mouth’. |

|

|

|

Admittedly this was after Einstein’s death, but Born had also written extensively about Einstein while he was alive, but apparently he couldn’t accept Moszkowski’s impulse to do the same. In any case, after all the sturm and drang, the appearance of Moszkowski’s book in 1921 didn’t inflict any appreciable damage on Einstein. In just a single year, over 100 books about Einstein and the theory of relativity were published, so it was only an incremental addition to the “publicity” that surrounded him for the rest of his life. From the modern standpoint, probably the most disreputable thing to make it into the published version was Einstein saying that although he favored giving women the opportunity for higher education he was doubtful that there would ever be many great women scientists. He joked that “It’s possible the Lord created a gender without brains”. |

|

|

|

Of course, the re-structuring of the book to make it seem less like a vanity project may have been helpful in ensuring that it just blended in with the other Einstein literature. In retrospect, Moszkowski’s book (at least in the heavily edited 1921 version) is actually quite valuable in the sense of providing interesting discussions of some genuine scientific and social issues and sidelights. One chapter, entitled “Beyond our Power”, gives a fascinating insight into the perceived dependence on coal as the source of energy for modern civilization, and on the perceived finiteness of this resource. Already in these early years of the 20th century there was a prevailing sense of uneasiness that a civilization based on such prodigious energy consumption might not be sustainable. Moszkowski makes it clear that much of the popular allure of the equation E = mc2 was due to the idea that this fantastic store of energy might somehow be exploited to support the ever-increasing energy demands after the coal supply was exhausted. The book also reveals not only Einstein’s skepticism in those days, but also his fears. |

|

|

|

Einstein, to whom we owe this formula so promising of wonders, not only denies that it can be applied practically, but also brings forward another argument that casts us down to earth again. Supposing, he explained, it were possible to set free this enormous store of energy, then we should only arrive at an age, compared with which the present coal age would have to be called golden. …if we should succeed in disintegrating the atom, it seems that we should have the billions of calories rushing unchecked on us, and we should find ourselves unable to cope with them… No discovery remains a monopoly of only a few people. If a very careful scientist should really succeed in producing a practical heating or driving effect from the atom, then any untrained person would be able to blow up a whole town by means of only a minute quantity of substance. And any suicidal maniac who hated his fellows and wished to pulverize all habitations within a wide range would only have to conceive the plan to carry it out at a moment's notice. |

|

|

|

At this point in the rather modern-sounding discussion, Moszkowski tells us that |

|

|

|

Einstein turned to a page in a learned work of the mathematical physicist Weyl of Zurich, and pointed out a part that dealt with such an appalling liberation of energy. It seemed to me to be of the nature of a fervent prayer that Heaven preserve us from such explosive forces ever being let loose on mankind! |

|

|

|

Presumably the “learned work” was Weyl’s “Space, Time, Matter”, first published in 1918. After describing the binding energy of the electrons in ordinary chemical reactions, Weyl noted that |

|

|

|

The energy of the composite atomic nucleus, of which a part is set free during radioactive disintegration, far exceeds the amounts mentioned above. The greater part of this, again, consists of the intrinsic energy of the elements of the atomic nucleus and of the electrons. We know of it only through inertial effects, as we have hitherto – owing to a merciful Providence – not discovered a means of bringing it to explosion. |

|

|

|

It’s interesting the Einstein would remember such a slight comment, and point it out to Moszkowski. Ironically, just a few months after this discussion took place, Rutherford succeeded in splitting the atom, an accomplishment that caused Einstein to re-assess the feasibility of eventually producing energy from atomic power. Moszkowski also noted that |

|

|

|

It seems feasible that, under certain conditions, Nature would automatically continue the disruption of the atom, after a human being had intentionally started it, as in the analogous case of a conflagration which extends, although it may have started from a mere spark. |

|

|

|

If nothing else, this shows that already by the end of the first world war, the general outline for atomic bombs, if such things were possible, was already fairly well known, and that people were already worried about the associated risks. It also shows that, in the popular mind, Einstein was already closely associated with the possibility of nuclear power. On a less ominous note, there’s an interesting passage in Moszkowski’s book on how Newton’s law of gravitational attraction at a distance was seen as an “occult” phenomenon by many scientists of that time. We tend to focus on the problematic aspects of “distant action”, but Moszkowski suggested that another potentially objectionable aspect of Newton’s law was that it involved an elementary attraction, whereas the materialism of most other scientists at that time sought to account for all phenomena in terms of pressure and impact, which somehow seem more intelligible (at least superficially). Einstein answered that he didn’t think this was a fundamental objection, because it’s possible to re-express a law of attraction in the form of a law of repulsion. According to Moszkowski, Einstein explained this as follows: |

|

|

|

If the force is exerted by a corpuscular transmission, we may imagine a “force-shadow” into which the bombarding corpuscles cannot penetrate. Thus if an obstacle, which produces such a shadow, becomes interposed between a body A and a body B, then there will be a lesser pressure on the side of B facing A, and hence B will experience a greater corpuscular pressure on the other side, with the result that B will be forced in the direction of A, and the observer would gain the impression of a pull from B to A. |

|

|

|

This must be a garbled version of what Einstein actually said, because it refers to interposing an obstacle between two bodies, whereas the actual theory Einstein is describing (which is the shadow-theory advocated by Newton’s friend Nicolas Fatio and, later, Georges-Louis Lesage) simply relies on the fact that each body itself casts a shadow onto neighboring bodies, and hence produces a net “attraction” from the imbalance of repulsive forces. (Incidentally, in 1905, immediately after completing his paper containing the relation E = mc2, Einstein had written a review of a paper by Karl Bohlin on a kinetic theory of gravitation, which was evidently similar to the Fatio-Lesage theory, except that Bohlin carried the idea to its logical conclusion, postulating an infinite regress of corpuscles of infinitely many orders of magnitude, accounting for both attraction and repulsion.) It’s fitting that Einstein, with his affection for Switzerland, should have remembered this invention of two of his Swiss predecessors, although it’s odd that he apparently didn’t mention either of them by name. The fact that the alleged quote describing the shadow theory is garbled shows, again, the unreliable nature of biographies. |

|

|