|

Spacetime Inversion |

|

|

|

The content of special relativity is that the laws governing the changes in state of any physical system are covariant under Lorentz transformations (as well as under translations and spatial rotations). In other words, relatively moving spacetime coordinate systems in terms of which inertia is homogeneous and isotropic are related by Poincare transformations. These are unique if we restrict ourselves to continuous and linear mappings, but the most general class of transformations that preserve the physical laws such as Maxwell’s equations also includes reflections and spacetime inversions. |

|

|

|

The necessary and sufficient condition for the invariance of many physical laws under a mapping from inertial coordinates is that all null spacetime intervals are preserved. (For example, it was shown in 1910 by Bateman and independently by Cunningham that invariance of Minkowski null intervals under a given coordinate transformation is the necessary and sufficient condition for Maxwell’s equations to be covariant under that transformation.) To prove the invariance of Minkowski null intervals under spacetime inversions, consider two events E1 and E2 that are null-separated from each other, meaning that the absolute Minkowski interval between them is zero in terms of an inertial coordinate system x,y,z,t. Let s1 and s2 denote the absolute intervals from the origin to these two events (respectively). Under an inversion of the coordinate system about the surface at an absolute interval R from the origin (which may be chosen arbitrarily), each event located on a given ray through the origin is moved to another point on that ray such that its absolute interval from the origin is changed from s to R2/s. Thus the hyperbolic surfaces outside of R are mapped to surfaces inside R, and vice versa. The ray from the origin to the event Ej can be characterized by constants αj, βj, γj defined by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In terms of these parameters the magnitude of the interval from the origin to Ej can be written as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

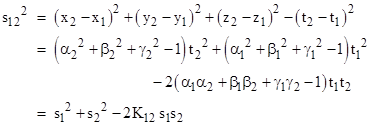

The squared interval between E1 and E2 can therefore be expressed as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

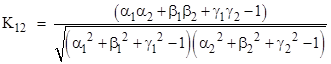

where |

|

|

|

|

|

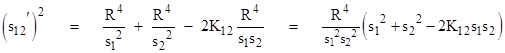

Since inversion leaves each event on its respective ray, the value of K12 for the inverted coordinates is the same as for the original coordinates, so the only effect on the Minkowski interval between E1 and E2 is to replace s1 and s2 with R2/s1 and R2/s2 respectively. Therefore, the squared Minkowski interval between the two events in terms of the inverted coordinates is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

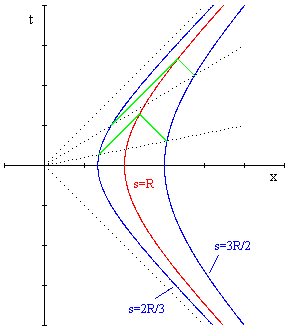

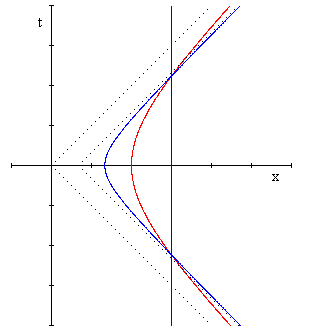

The quantity in parentheses on the right side is just the original squared interval, so if the interval was zero in terms of the original coordinates, it is zero in terms of the inverted coordinates. Thus inversion of a system of inertial coordinates yields a system of coordinates in which all the null intervals are preserved. (More generally, the quantity s122/(s1s2) is preserved under spacetime inversion.) This is illustrated in the figure below, which shows two surfaces that map to each other under inversion about the s=R surface. Of course, the s=R surfaces maps to itself under this inversion. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The rays from the origin also represent the states of Born rigid motion of a rigid rod accelerating uniformly in the x direction. The figure above shows that the geometric mean hyperbola (i.e., the locus s=R) plays the role of the “mid-point” of the accelerating rod extending from s=2R/3 to s=3R/2, in the sense that pulses of light emanating from the end-points “simultaneously” (with respect to the rod’s instantaneous inertial rest frames) arrive at the s=R locus simultaneously. |

|

|

|

Another important property of spacetime inversion is that straight lines in the inertial coordinate system map to hyperbolic paths under inversion. This corresponds to the fact that, according to the Lorentz-Dirac equations of classical electrodynamics, perfect hyperbolic motion is inertial motion, in the sense that there are free-body solutions describing particles in hyperbolic motion, and a charged particle in hyperbolic motion does not radiate. To prove that inertial paths map to hyperbolic paths, note that any inertial path (in flat spacetime) is of the form x = constant, y = z = 0 for some system of inertial coordinates whose origin is any chosen center of inversion. The absolute squared interval between the origin and this inertial path is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now let X(t) and T(t) denote the inverted coordinates of this path relative to the inversion surface of radius R. The squared interval between the origin and this path is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

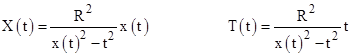

where, by the definition of spacetime inversion, we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

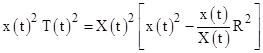

From these relations it follows (up to reflections) that |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

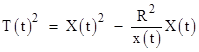

Solving the left hand relation for t2 we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Substituting this into the equation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

gives |

|

|

|

|

|

Dividing through by x(t)2 and simplifying, we get |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

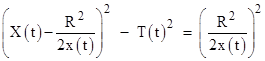

Completing the square on the right side and re-arranging terms, this can be written in the form |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

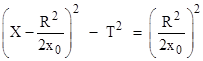

By construction the value of x(t) is a constant x0, and we can suppress the parametric arguments on X and T, so the inertial path in terms of the inverted coordinates has the hyperbolic equation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus the center of the inverted inertial path is offset from the center of the surface of inversion (half way between the origin and where the inverted locus crosses the x axis). A plot of an inertial path and its hyperbolic inversion is shown below. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|