|

Generalized Mediant |

|

|

|

Please help me undo this button. Thank you, sir. Do you see that? Look at her. Look, her lips. Look there, look there. |

|

|

|

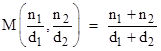

Given any two fractions n1/d1 and n2/d2, the mediant is defined as the fraction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

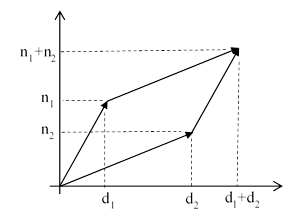

Graphically, we can regard each fraction n/d as a vector with the components (d,n), and then the mediant is simply the vector sum of two given fractions, as shown below |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

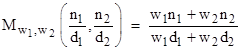

The locus of fractions with a given numerical value q is obviously the straight line through the origin with slope q, so it's clear that the value of the mediant is strictly between the values of the two original fractions. Also, the mediant has the same value as the average of the two vectors, since the ratio of (n1+n2)/2 and (d1+d2)/2 has the same value, (n1+n2)/(d1+d2), as the mediant. It's also clear that for any two positive real numbers w1 and w2 the weighted mediant defined as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

has a value that is strictly between the values of the arguments. |

|

|

|

Incidentally, notice that it's important to distinguish between the concepts of "fraction" and "ratio". A fraction is an ordered pair of real numbers, whereas a ratio is a single real number. We can regard each ratio as an equivalence class of fractions. For example, the ratio 3 includes the fractions 3/1, 4.5/1.5, 12/4, and so on. However, the various members of an equivalence class yield different results under the mediant operation, as shown by the fact that M(3/1,1/1) = 4/2 whereas M(6/2,1/1) = 7/3. |

|

|

|

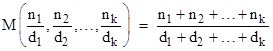

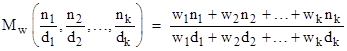

We can obviously generalize the mediant concept to any number of fractions n1/d1, n2/d2,..., nk/dk, and define the mediant as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Again we see that the mediant represents the vector sum of the individual arguments, interpreted as vectors, and again the sum lies along a line through the origin that also passes through the geometrical midpoint (center of gravity) of the points (dj,nj), j=1,2,..,k. It follows that the value of the mediant is strictly between the extreme values of the arguments. (This inequality was first pointed out by Cauchy.) Furthermore, the same is true even if we apply arbitrary positive "weights" w1, w2,...wk to give the weighted mediant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Since the general mediant always yields a result whose value is strictly within the range of the arguments, we can use mediants to define a contractive mapping, and iterate this mapping in a way similar to the celebrated arithmetic-geometric mean, or James Gregory's geometric-harmonic mean. (See Iterated Means.) |

|

|

|

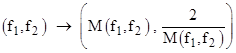

To give a simple illustration (suggested by D. G. Morin), suppose we wish to compute rational approximations to the square root of 2. If we begin with two numbers whose product is 2, and produce successive pairs of numbers that are progressively closer to each other and whose product remains equal to 2, we will approach values equal to √2. To accomplish this, we can apply the mapping |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

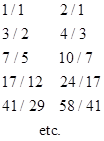

Beginning with the two fractions 1/1 and 2/1 we produce the sequence of pairs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note that 2/M(f1,f2) equals the weighted mediant M2,1(f1,f2). In general, to construct a sequence for the square root of an arbitrary number x we can begin with two fractions f1 = a/b and f2 = xb/a whose product is x, and then iteratively apply the mapping |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus the mapped fractions are |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and hence we have f1 = a/b and f2 = xb/a where |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In matrix form this can be written as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Letting L denote the coefficient matrix on the right side, we see that Ln generates the sequence of pairs, as shown below for the first few powers with x=2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

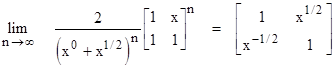

We also have the limiting identity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

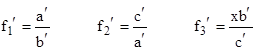

for any positive value of x. The same approach can be applied to roots of any order. For example, to compute rational approximations of the cube root of x, we can begin with the three fractions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

whose product is x, and then map them to the triple of weighted mediants |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

whose product is also x, and which has the same form as the original triple, i.e., |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where |

|

|

|

|

|

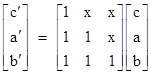

In matrix notation this can be written as |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

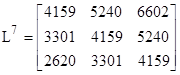

Letting L denote the coefficient matrix on the right side, we see that Ln approaches a counter-symmetrical matrix whose components differ by a factor of x1/3 in both the vertical and horizontal directions. For example, with x=2 we have |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

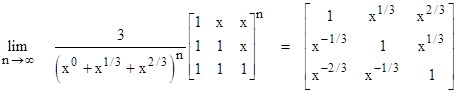

We also have the limiting identity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

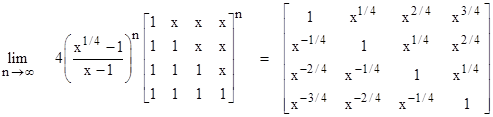

for any positive value of x. The analogous results apply to higher order system. For example, substituting for the geometric series in the denominator on the left hand side, we have the 4th order identity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We can also populate the lower triangular region with some other constant y, in which case the terms in the matrix on the right hand side differ by factors of (x/y)1/4. However, the normalizing factor is more difficult. |

|

|